CHAPTER TWO

PRIVATE

PATRONAGE

& CULTURAL

DEMOCRACY

68 Howard Greenfeld, Ben Shahn: An Artist’s Life (Lexington: Plunkett Lake Press, 2019), 52.

In early 1928, painter and lithographer Ben Shahn sailed from New York to France with his wife, Tillie. Their eventual destination was the small island of Djerba, off the coast of Tunisia, which offered Shahn the isolation he felt he needed to be able to develop his voice and style of painting away from the competitive artistic communities of Paris or New York. After spending a year on Djerba, the couple traveled to Spain for a few weeks before finally ending up back in Paris, where Tillie was due to give birth to a child in the summer of 1929.68

69 Ben Shahn, Oral history, interview by Harlan Phillips, October 3, 1965, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution. 70 Ben Shahn, Oral history, interview by Harlan Phillips, October 3, 1965, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution.

Shahn had earned enough money from selling some of the more than two hundred drawings and watercolors he had produced to last for more than a year and half in Europe, but when the baby arrived, he and Tillie were nearly out of money. They returned to New York in late October 1929 and settled back into their Brooklyn Heights apartment. Shahn had planned to find work in printmaking, as he had trained as a lithographer earlier in his career and had previously never had trouble getting a job.69 However, he reentered the New York art market at exactly the wrong time: the stock-selling frenzy that had started earlier in October was about to culminate in the largest stock market crash in U.S. history, launching the Great Depression. “When I came back, there weren’t any jobs and my knees shook…I came back with a baby; that was the other thing. So I shook, it was a terrifying experience,” he recalls.70 His fellow printmakers warned him that because he had been out of the country for much of the 1920s and away from his lithography work for over four years, even if there were jobs to be had, they would go to those who had replaced him.

71 Howard Greenfeld, Ben Shahn: An Artist’s Life (Lexington: Plunkett Lake Press, 2019), 55.

With commercial and advertising jobs gone, Shahn was forced to try to make a living as a painter. Even before the crash, there were only a handful of New York art galleries that would sell works of American artists who painted in contemporary styles, as their elite clients preferred the academy style of the European masters. Afterward, customers for American contemporary art were incredibly scarce.71 Shahn left his work at galleries across the cities to no avail—there was simply no demand.

72 Howard Greenfeld, Ben Shahn: An Artist’s Life (Lexington: Plunkett Lake Press, 2019), 57. 73 Ben Shahn, Oral history, interview by Harlan Phillips, October 3, 1965, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution.

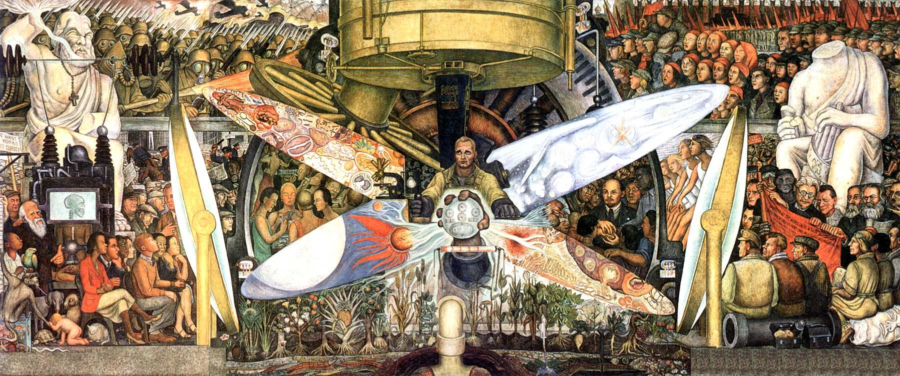

One of those galleries was the Downtown Gallery in Greenwich Village, owned by art dealer Edith Halpert. After hearing no response for several weeks, Shahn tried to contact Halpert, but, inundated with work from unemployed artists, she had not had time to look at his paintings. But a few days later, miraculously, he received a telegram asking for more of his work. He later learned that Abby Rockefeller, wife of John D. Rockefeller, Jr., had seen his paintings while at the gallery and purchased several on the spot.72 Eventually, the chance encounter led to an exhibition. Shahn found some other odd jobs after that, including assisting Diego Rivera on Man at the Crossroads in Rockefeller Center, the mural destined to be destroyed by Abby’s son, Nelson. But by early 1934, he was out of work again.73 Later that year, he managed to get on the Public Works of Art Project (PWAP), which only lasted for a few months. By July 1935, he was unemployed once more.

Shahn was one of the most successful—and luckiest—artists in the New York scene during the early years of the Depression, and even he found earning a living as an artist to be extremely capricious, difficult, and stressful. The vast majority of other artists found that any hope of wealthy private patrons buying their work had vanished almost overnight, along with the fourteen billion dollars of stock lost on Black Tuesday. In the January 1935 issue of Art Front, the Artists Union—of which Shahn was now a member—explained the dire situation:

74 “Artists Union Federal Art Bill,” Art Front, January 1935, 2.

With the deepening of the economic crisis, the artist’s traditional poverty has become acute. Private patronage has almost disappeared. Increasing numbers of artists are on relief rolls, unable to buy materials, scarcely able to exist on the meager sum allowed them. Some attempts have been made to alleviate the artist’s condition through art work relief, either publicly or privately supported. Such relief has been temporary and insecure. The jobs are soon ended, the artists left more desperate than before.74

The desperation for artists was so acute that the union was occasionally called upon to send a delegation to the offices of the Home Relief Bureau in support of artists who were in danger of being evicted but whose applications for assistance had been rejected. The artistic community could not survive in a system based only on private patronage when there were hardly any private patrons to be found.

75 Stuart Davis, “The Artist Today: The Standpoint of the Artists’ Union,” The American Magazine of Art 28, no. 8 (1935), 476.

Artist Union member and Art Front editor Stuart Davis provided further detail on the exploitative reality of the pre-Depression art world in the August 1935 issue of The American Magazine of Art. The Artists Union, he announced, was aiming to work against “the immediate past of the American fine-artist.” These artists came from middle- and upper-class families that could afford (typically European) art schools, which were also middle- and upper-class in nature, and naturally produced art that appealed to middle- and upper-class audiences—namely, still lifes, landscapes, and nudes. Their art was sold through art dealers to galleries, private patrons, and museums. By charging commissions, the art dealer was able to offer their business to a myriad of artists at no cost to himself, promising affluence once their paintings made it into galleries, while the artists were forced to pay various gallery fees and received only a maximum of two-thirds of the sale price after commissions were deducted. Each gallery found a few artists who proved to be commercial successes—usually those who relied on safe, conventional subjects and media—and excluded the others, especially contemporary artists. As Davis concludes, the market was run on “art for profit, profit for everybody but the artist.”75

76 Sharon Zukin, “Art in the Arms of Power: Market Relations and Collective Patronage in the Capitalist State,” Theory and Society 11, no. 4 (1982), 426. 77 Sharon Zukin, “Art in the Arms of Power: Market Relations and Collective Patronage in the Capitalist State,” Theory and Society 11, no. 4 (1982), 424. 78 “Letters from Our Friends, Art Front, November 1934, 2. 79 “The Sidewalks of New York,” Art Front, July 1935, 3.

While Davis was obviously biased in his view of American art patronage, contemporary sociologist Sharon Zukin concurs. Until the early twentieth century, “the ‘best’ art in museums reflected patrician support and patrician sensibility,” she writes.76 The art dealers who came to be detested by Davis had entered the scene in the 1870s, encouraged by the growth of a new middle class eager to establish its status through participation in the art market. But when the Great Depression hit, “the arts moved from being a marginal and often elitist concern to being a central social symbol.”77

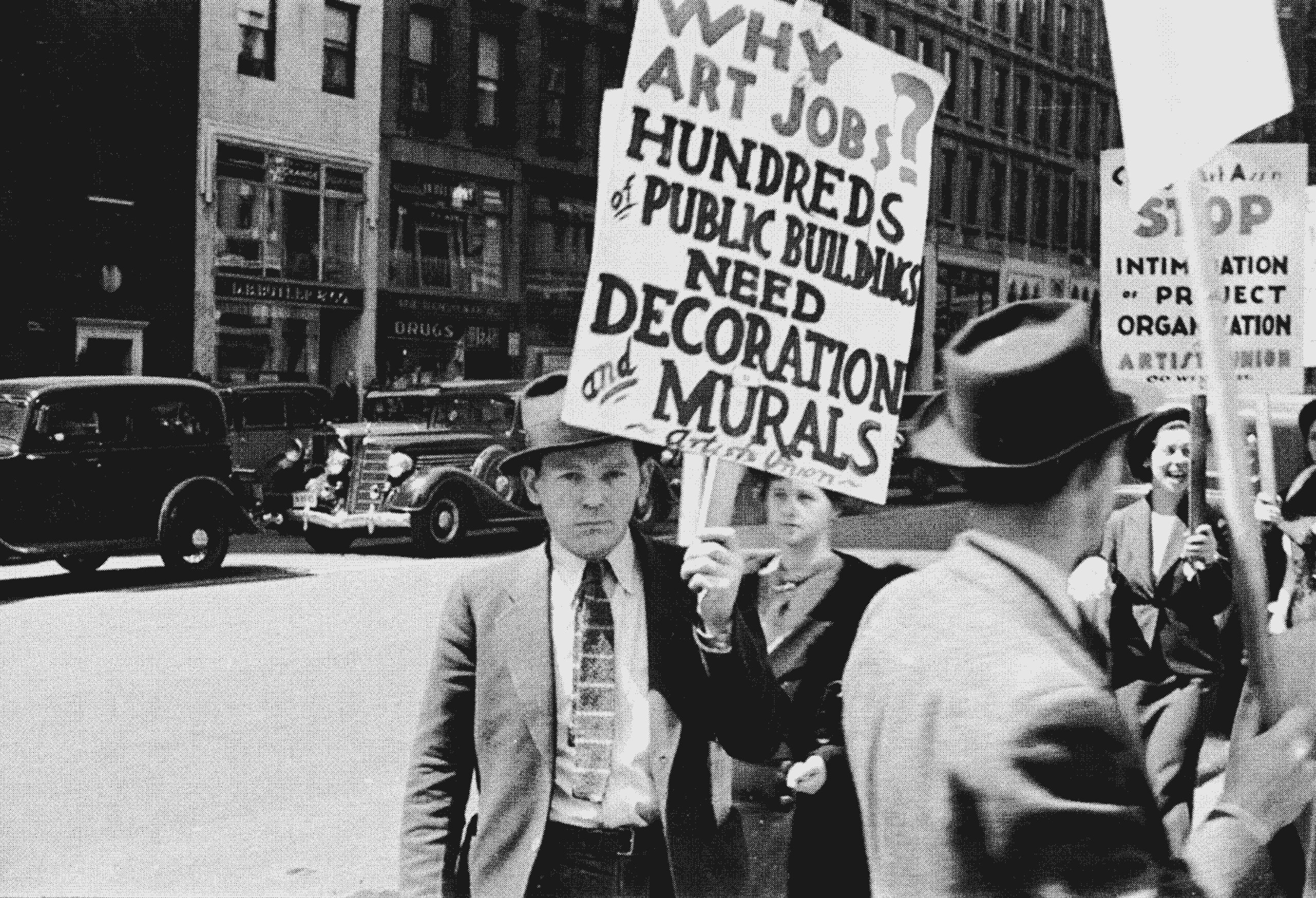

This transition was driven in large part by the Artists Union, which, in the wake of the disappearance of wealthy private patronage, demanded that local, state, and federal governments step in to save the floundering art community. The union saw public support as an opportunity to advance both pragmatic goals, such as establishing relief programs to employ artists in their field to alleviate economic suffering, and ideological ones, such as creating public space for art and artists through building art centers that would cultivate the artistic community, provide a space to display art in competition with posh galleries, hold events, and house studios and art education. Creating public spaces for art and artists was the principal manifestation of the union’s core ideological belief in cultural democracy—the idea that all people have the right to have access to culture that is diverse in thought and stylistic expression. The Artists Union had a particular interest in promoting this shift in thinking, since it positioned the art that its members were producing as something that could be enjoyed by everyone on a daily basis rather than a rarity that was only in the purview of the rich. As the union gained prominence, it sought to establish “a healthy relationship between the artist and the community” by taking art directly to the people and promote the idea that an authentic, bottom-up, even autodidactic approach was necessary for the distinctly American style of art originally proposed by the editors of The Liberator and heavily adopted among union members. This, they argued, would “free art from the false and unsocial pecuniary standards that now so largely dominate its patronage and employment.”78 Bringing art to ordinary people did more than just foster a genuine working-class cultural movement, however. There was altruistic benefit, the union argued, in simply bringing decoration and vitality to the decrepit, miserable libraries, schools, and hospitals that served the city’s poorest neighborhoods.79 This was undergirded by a general moral stance of helping the most vulnerable in society—certainly influenced by the union’s affinity for socialism—and public art was the best way that union members could contribute.

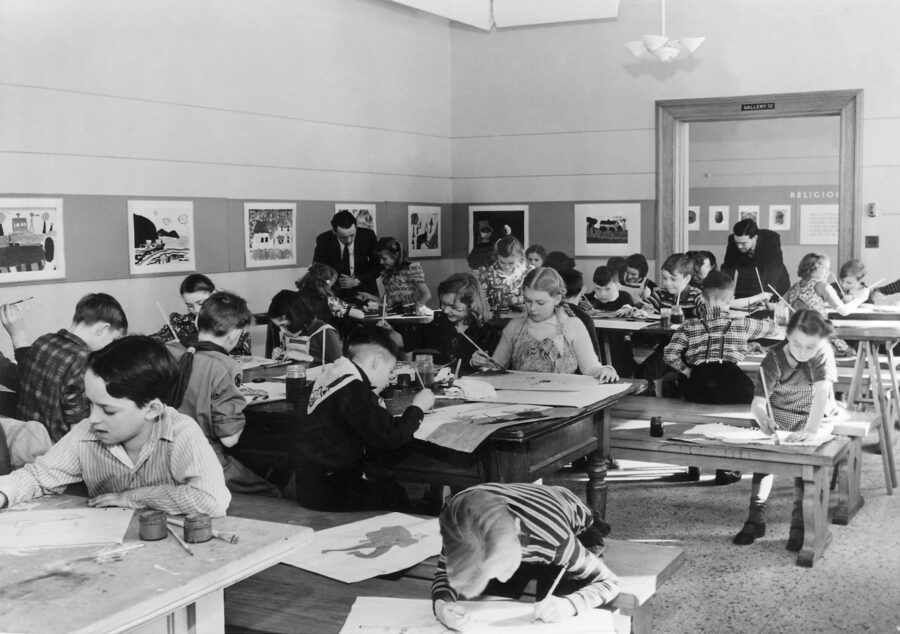

Aside from their belief in the intrinsic value of art in civic life, Artists Union members had a vested interest in promoting the appreciation of art and art education: they were creating new audiences for their own work. This strategy is still in place among cultural organizations today—art museums, ballet companies, and symphony orchestras offer lessons and workshops, especially for children and youth, to create an audience for the work of professionals. The union’s promotion of public art education also meant that ordinary Americans had the opportunity to become artists and see art as something that they could make, rather than regarding it as something that got produced by elites, for elites.

80 “Letters from Our Friends,” Art Front, November 1934, 2. 81 Edward Alden Jewell, “In the Realm of Art: First Municipal Art Exhibition at Rockefeller Center,” The New York Times, March 4, 1934, sec. Art, 12.

The union’s campaign to make art part of people’s daily routine, bringing “painting and sculpture as close to them as the moving pictures and the comic strips now are,” began in earnest in mid-1934 with a campaign to build a municipally funded art center in New York City.80 This was a groundbreaking proposal, as sponsorship of the arts by the New York City government was a relatively new phenomenon—the first instance had occurred only months earlier, when the first municipally sponsored exhibition opened at Rockefeller Center on February 28, 1934.81

82 Daniel Okrent, Great Fortune: The Epic of Rockefeller Center (New York: Penguin, 2004), 313. 83 “Rivera RCA Mural Is Cut From Wall,” The New York Times, February 13, 1934, 21.

It was at that very exhibition where the urgent need for a public art center first became clear. The complex was the site of Diego Rivera’s famous Man at the Crossroads mural, which had been destroyed on orders from Nelson Rockefeller about two weeks earlier because Rivera refused to remove a portrait of Vladimir Lenin—having been encouraged to stand his ground by union member Ben Shahn.82 At midnight on Saturday, February 10, workers had removed the cream-colored canvas that was concealing the work, hacked out the plaster on which the mural was painted, and replastered it.83

84 “Jonas Lie and Property Rights,” Art Front, November 1934, 3; “Municipal Art Gallery and Center,” Art Front, November 1934, 6. 85 “Municipal Art Gallery and Center,” Art Front, November 1934, 6. 86 “Municipal Art Gallery and Center,” Art Front, November 1934, 6. 87 “Municipal Art Gallery and Center,” Art Front, November 1934, 6. 88 “Municipal Art Gallery and Center,” Art Front, November 1934, 6.

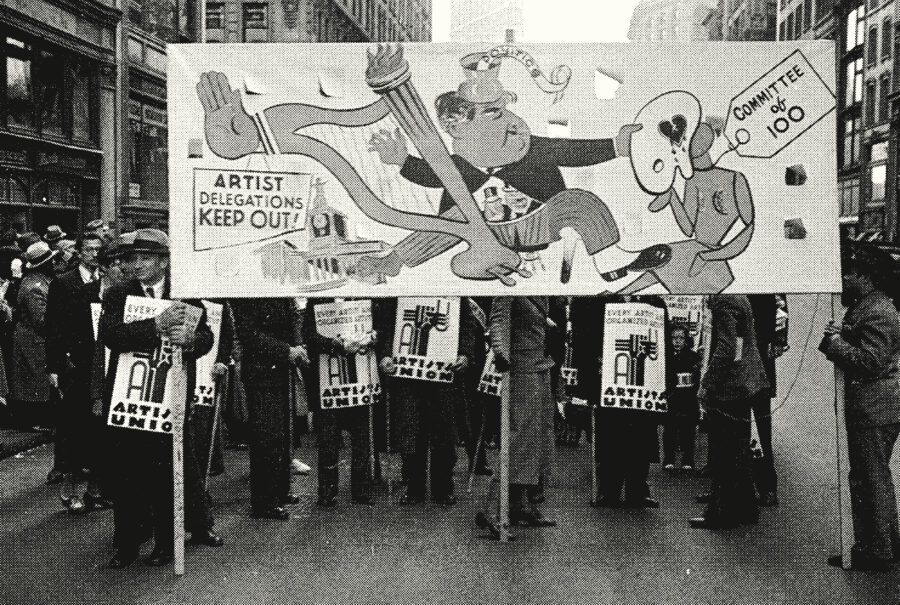

Understandably, artists were enraged. When the municipal exhibit opened, the Artists Union set up a picket line to protest, and many artists tried to withdraw their works.84 According to the union, “every conceivable method was used to break down this revolt of the artist.”85 They alleged that gallery owners and museum administrators threatened to boycott artists who withdrew their work and that Rockefeller’s associates gave false statements to the press about Rivera’s willingness to have the work destroyed rather than compromise his message and vision—although the stories of Rivera’s devotion to his cause were later revealed to be true.86

The union initially planned a counter-exhibition in retaliation, but soon realized that a more permanent, public solution was needed. The artists needed the steady, guaranteed financial support of the government without being subject to bureaucrats or wealthy benefactors dictating content or style. Their solution was to propose an unprecedented commitment of public money to the arts: a municipal art gallery and center, “solely under the control of the artists.”87 This was motivated by the artists desire both to remedy their financial needs and to move toward cultural democracy, even if this was a small step. A twenty-point outline was developed by union members with requirements ranging from the ideological—declaring there would be no discrimination against any aesthetic style, political affiliation, race, creed, or color—to the practical—organizing the different subsections of the center, like the meeting place, studios, laboratories, and center for traveling exhibitions.88 Small delegations of the Artists Union and Artists Committee of Action brought the proposal to the Mayor LaGuardia’s office repeatedly, but never made it further than his secretaries’ desks.

The union resolved to organize mass action to impress upon the city government the importance of public art. A meeting was scheduled for the evening of May 8, 1934 at the New School for Social Research at 66 West 12th Street. Hundreds of artists, representatives of art organizations, and art lovers gathered in the newly opened auditorium designed by Joseph Urban. The groundbreaking space, now seen as one of the first examples of modernist interior architecture, played perfect host for the inspired, historic spirit of the evening, as union members and other guests made rousing speeches about the importance of cultural democracy and took part in lively debate over the plan for what they hoped would be the first instance of large-scale, permanent government patronage of the arts in New York City and a model to be followed across the country. Eventually, a resolution was adopted that generally mirrored the original outline for the gallery and center, emphasizing four main points:

89 “Municipal Art Gallery and Center,” Art Front, November 1934, 6.

- A permanent Art Gallery for all New York Artists

- A circulating library for pictures and sculptures

- No jury system, no discrimination against creed or color

- Administered by and for the artists89

90 “300 Artists Demand Municipal Centre; Deutsch Pledges Aid to Group at City Hall,” The New York Times, May 10, 1934, 24. 91 “Artists to March to City Hall,” The New York Times, May 8, 1934, 21; “Municipal Art Gallery and Center,” Art Front, November 1934, 6.

The next day, roused by the heady events of the meeting, 300 artists marched from their headquarters on 11 West Eighteenth Street to City Hall a few blocks away, beating drums and clashing symbols along the way to draw attention, which eventually helped expand the crowd to several hundred more.90 The President of the Board of Aldermen, Bernard Deutsch, met with a delegation from the union, received the proposal, and promised to use his influence to lobby for the project, advising the union to try to locate an empty building suitable for the center.91

For the next five months, the union was given the run-around by various municipal departments, which was humorously recounted in the pages of Art Front:

92 “Municipal Art Gallery and Center,” Art Front, November 1934, 6.

From the secretary of the Mayor, Mr. Dunham, to the President of the Board of Aldermen, Mr. Deutsch. From Mr. Deutsch to the Sinking Fund Commissioner. From the Sinking Fund Commissioner to the Park Department. From the Park Department to the Board of Education. From the Board of Education to the Welfare Department. From the Welfare Department to the Port Authority. From the Port Authority back again to Mr. Deutsch.92

93 “A Set of Plans,” Art Front,February 1935, 2.

The union was far from dormant during this time—it continued to protest at City Hall, pressuring the mayor who repeatedly cancelled appointments with union delegations, and even commissioned members of the Federation of Architects to draw up plans on how an unused public building could be converted into a municipal art center.93

94 “Plans for Auditorium and Art Center To Be Announced by Mayor Tomorrow,” The New York Times, December 15, 1935, 42. 95 “Civic Art Centre Planned By Mayor; Committee of 118 Named in What Is Held Initial Step in His Program,” The New York Times, January 7, 1935, 1. 96 “LaGuardia Ignores Demands of Artists; Mayor Refuses Reply to Letter of Committee Demanding Municipal Gallery,” The New York Times, November 3, 1934, 7. 97 Alfred Sinks, “Potted Palms and Public Art,” Art Front, February 1935, 4.

On a cold Sunday evening in January 1935, however, the throngs of unemployed workers applying for relief that normally dominated City Hall Park were replaced by limousines. Mayor LaGuardia had gathered 118 members of the New York City art community to form a Municipal Art Committee to stimulate “the artistic life and expression of the city.”94 Much to the dismay of the union, the roster was dominated by Astors, Guggenheims, Whitneys, and Vanderbilts, although the union did have a few allies among the tycoons and socialites, including former New Masses contributor Louis Lozowick.95 The committee, Mayor LaGuardia announced, would be responsible for developing a municipal art center, an idea he had apparently conceived of despite repeatedly ignoring plans and letters sent by union members.96 Understandably, his announcement drew the ire of union members who had spent months working on the project only for Mayor LaGuardia to swoop in at the last second and claim the credit:

Even the artist or two present were awed, for they were thinking about the months of struggle for a Municipal Art Center by the Artists Committee of Action and the Artists Union. They thought of the gigantic effort that had been expended to organize the artists into a united force to make the city rulers see the need of such a center, of the cooperation of the Federation of Architects who had labored over a complete set of plans for the conversion of a city owned building now unoccupied, of the delegation after delegation that had been sent in vain attempts to bring the project to the attention of the Mayor, of the quantities of mail sent by artists which had never been answered or apparently read, and here—like an unscheduled shaft of Jove’s lightning cracking down from high Olympus—came this amazing and original inspiration from Mr. LaGuardia himself!97

Although Mayor LaGuardia used the announcement of the center to bolster his own reputation as an advocate of the art community, the fact that there had been a meeting in the first place was proof of the union’s ability to organize artists and put pressure on the government to work towards doing away with private patronage.

98 Alfred Sinks, “Potted Palms and Public Art,” Art Front, February 1935, 4. 99 “‘We Reject’ —The Art Commission,” Art Front, July 1935, 4.

In keeping with its commitment to ending the elites’ control over art, the union immediately made it clear that, due to its high numbers of loathed wealthy patrons, the committee would only be welcomed in an advisory role; management and decisions about projects should be made by artists only.98 That was not the intention of the Mayor’s office, of course, and it did not take long for the union and the committee to begin to butt heads. In early 1935, a mural designed by union members Ben Shahn and Lou Block to be placed in the Riker’s Island Penitentiary was rejected by the commission, leading to a scathing editorial titled “‘We Reject’ —The Art Commission” in the July 1935 issue of Art Front.99

100 “Municipal Art Gallery,” Art Front, January 1936, 4.

After months of red tape and government inaction, and despite substantial private donations, it became apparent that the state of the city’s finances, burdened by unemployment relief, could not support LaGuardia’s proposal. The union’s vision for a permanent municipal center would not be realized for a considerable time, if ever. The union was able to secure some aspects of its original plan: the Municipal Committee sponsored a handful of temporary exhibitions throughout 1935 as well as a small program to bring art to some of the city’s poorest communities, which employed nearly 300 artists to teach painting and drawing, decorate public buildings like schools and hospitals, and design posters for tax-free or tax supported institutions. According to the January 1936 issue of Art Front, it “succeeded in interesting thousands of children and adults who never had an art education.”100

101 “Cracking Down,” Art Front, May 1935, 2.

At the same time, the union was also demonstrating its ability to defend the few members who were employed and continuing its campaign for fair working conditions for artists. In mid-1935, when the College Art Association (CAA) was managing a few small relief projects in New York, two union artists, Florence Lustig and Bernard Child, were fired for campaigning for union wages, protesting docked pay for sickness, and helping mobilize union members to reinstate two other artists had been wrongly terminated. On a Saturday morning, the union staged a picket line on the sidewalk outside the CAA offices, causing such an inconvenience that tenants of the building complained to the landlord, who threatened to evict the CAA, and a nearby drugstore and beauty parlor threatened to sue for loss of business.101 The union was given the “run-around” between various administrators, but continued to apply pressure and the two artists were eventually reinstated.

102 “City Art Gallery Opened by Mayor,” The New York Times, January 7, 1936, 19. 103 “‘Our’ Municipal Art Gallery and Center,” Art Front, February 1936, 4.

Even as it faced the demise of its hopes for a permanent municipal art center, the union kept pushing. On January 6, 1936, after over eighteen months of continued advocacy and direct action, the union won a partial concession when the city agreed to open a temporary Municipal Art Gallery in a city-owned brownstone at 62 West 53rd St.102 True to its nature, however, it immediately took issue with two clauses that appeared in the application to have work exhibited: the first was a rule that prevented non-citizens from showing work, the second was a note from the administration reserving the right to forbid pictures that they deemed offensive. The union voted to boycott the show, and two groups of union artists scheduled to exhibit sent telegrams to withhold their work until the clauses were eliminated. The next day, a union delegation was called in and told that their demands had been met.103

104 “Self-Government and the Municipal Art Center,” Art Front, February 1936, 6

For at least another few months, the union continued to fight for a circulation library and art school, not included in the original center, greater artists control of management, and to make the center and gallery permanent.104 While no member ever admitted it, the union likely gave up on its vision, as stories of struggles for a permanent municipal art center gradually disappeared from Art Front’s pages. The union was surely tired of the city’s resistance and frustrated by the Mayor’s office dragging its feet time and time again, but its attention and resources were also distracted by the campaign for a federal art work relief project, whose likelihood of success was becoming greater.

The Municipal Art Center served as a proof of concept for both the union’s ideological belief in the benefits of cultural democracy and its practical strategies of organizing. The constraints on New York’s municipal budget, however, meant that even successful advocacy was unable to produce sufficient relief, no matter the political will. The union needed to go to the lender of last resort—the U.S. government. A federal project could help more people and have the support and resources of Artist Union chapters across the country. New York artists weren’t the only ones who were suffering, after all.

105 “Why A Federal Art Bill,” Art Front, January 1935, 2.

The Artists Union first developed a Federal Art Bill after the end of the early New Deal Public Works of Art Project (PWAP) in early 1934, and a draft appeared in the second issue of Art Front in January 1935 with a solicitation for additional suggestions from artists and art organizations. After the PWAP, artists had entered “the sixth bitter winter of the depression” with no relief program or jobs on the horizon, and hoped to have a Federal Art Bill introduced in Congress to provide permanent relief.105 At the time, the Treasury Department sponsored a work program for artists, but it employed a limited number of artists who worked on commission and were chosen based on merit, and whose subject matter and style were heavily supervised—all things the Artists Union denounced on both artistic and ideological grounds.

106 “The Bill,” Art Front, January 1935, 2.

The union’s bill was largely presented as an extension of the PWAP—the country would be divided into the same regions and beginning pay would be placed at $38.25 for a thirty-hour work week, the same as had been paid to New York artists during the PWAP. The union’s bill attempted to address the PWAP and Treasury program’s faults by requiring that relief be given based on need, rather than artistic merit, adding that “it is no one’s office to pronounce upon what is and what is not art.”106 Using the model of the Municipal Art Center, the Union’s bill also proposed the construction of a permanent regional art center in each of the sixteen regions.

107 “Why A Federal Art Bill,” Art Front, January 1935, 8. 108 “Why A Federal Art Bill,” Art Front, January 1935, 2; “What Now, Mr. Bruce?” Art Front, January 1935, 3; “Artists on Work Relief,” Art Front, January 1935, 4. 109 “What Can the Artists Do?” Art Front, January 1935, 8.

Much like the union’s campaign for the Municipal Art Center, the objective of the bill was twofold: it not only provided economic security for the artist, but also intended to “acquaint the public with art, educate the public taste and make original art available to all people,” through exhibitions, lectures, discussions, monographs, and art literature.107 This commitment to art for the public, although undoubtedly useful in promoting the bill to government administrators and non-artists, was genuine. A number of Art Front articles from this period emphasize the public value of art despite the fact that its audience, nearly all members of the art community, did not need to be convinced of the importance of the bill.108 The magazine encouraged artists to request copies of the bill, sign the petition that would be attached to the mailed copies, form local organizations to present the bill to legislators, and send letters to President Roosevelt, senators, and congressmen.109

110 T. H. Watkins, The Hungry Years: A Narrative History of the Great Depression in America (New York : Henry Holt & Co., 1999), 259.

In January 1935, before the bill could even make it to Congress, President Roosevelt announced during his State of the Union address his plans to rework the current suite of relief programs, moving away from “the dole,” or receiving money without work, to work programs, proclaiming that “I am not willing that the vitality of our people be further sapped by the giving of cash…We must preserve not only the bodies of the unemployed from destruction but also their self-respect, their self-reliance and courage and determination.”110

111 T. H. Watkins, The Hungry Years: A Narrative History of the Great Depression in America (New York : Henry Holt & Co., 1999), 259.

Roosevelt asked Congress for $4 billion in addition to the $880 million still unspent from previous relief programs. The bill passed the House quickly, was debated in the Senate for only a few weeks longer and was signed by the president on April 8, 1935. Less than a month later, Harry Hopkins was named the chief administrator of the work program that would become one of the New Deal’s most enduring legacies: the Works Progress Administration (WPA).111 Of the $4.8 billion in total funding, $27 million was allocated for Federal Project Number One, or simply Federal One, which was comprised of five divisions: the Federal Music Project, the Federal Theatre Project, the Federal Writers' Project, the Historical Records Survey, and most importantly for the Artists Union, the Federal Art Project (FAP).

112 Max Spivak, Oral history, interview by Harlan Phillips, 1965, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution.

Unlike the PWAP, the FAP was a federal program from top to bottom, so there would only be a single head administrator for the New York area. The choice eventually came down to Juliana Force, whose unpopular leadership of the short-lived PWAP had made her a constant target for demonstrations, or the director of the College Art Association, Audrey McMahon. McMahon, more qualified and more popular among her prospective employees, eventually won out, much to the union’s benefit.112 By the beginning of August, she had aggregated all of the miscellaneous art projects in New York City under the umbrella of the FAP and had begun expanding them.

113 Harry Knight, Oral history, interview by Harlan Phillips, 1965, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution; Max Spivak, Oral history, interview by Harlan Phillips, 1965, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution.

It’s unclear how much impact the union had on the initial plan for the FAP, if any—they could not employ the effective types of direct action used to advance the Municipal Art Gallery for a nationwide, federal project, and Roosevelt’s urgent request for new work programs didn’t allow much time to garner support for the union’s version of a federal art bill. Yet many of the major influences in Roosevelt’s art administration, such as McMahon and FAP national director Holger Cahill, former director of the Museum of Modern Art, and director of some of the temporary municipal exhibitions, came from the New York City art community and were often in contact with the union. Naturally, they were attuned to the artists’ demands, or were even artists themselves.113

114 Gerald M. Monroe, “The Artists Union of New York” (Dissertation, New York, New York University, 1971), 12.

The structure of the FAP largely followed the union’s proposed bill, although it was less lucrative for the artists. Community art centers, traveling exhibitions, art education, and decoration of public buildings, all part of the union’s federal art bill, became central tenets of the FAP. Once the program was in place, the union’s organization and strength in negotiations with government administrators—skills they had honed over the past few years as they demonstrated at the Whitney to coerce Juliana Force into hiring union artists to extend the PWAP, pushed for a Municipal Art Center, and continually mobilized to reinstate fired artists—ensured that the FAP lasted longer and employed more people than intended.114 The result was more art produced and seen by ordinary people—an important factor in the union’s quest for cultural democracy.

After the FAP was up and running, jobs for artists skyrocketed, at least relative to the previous scarcity of work. Max Spivak and Hugo Gellert were designing murals, Boris Gorelick was making prints, and Bendor Mark was oil painting—all union members. In fact, the union appears to have been so busy that no issues of Art Front were released between June and November 1935. There were some complaints of delays in projects being assigned, especially outside of New York, but it wasn’t because the money wasn’t there. It was simply the struggle of federal administrators to organize a massive bureaucracy in only a few short months. At its peak in 1936, the FAP had expanded to employ around 5,000 artists.

115 Morris Neuwirth, “219!” Art Front, January 1937, 4. 116 Morris Neuwirth, “219!” Art Front, January 1937, 4.

Just as it seemed the artistic community would be saved, at least momentarily, trouble arose. President Roosevelt, seeing an upturn in the economy, told WPA administrators to reduce the number of workers on their payrolls in late 1936, expecting that those jobs would be moved to private industry as companies had more money. Artists, however, had no private industry to return to, and were determined to do everything in their power to keep the FAP at full capacity despite an announcement in mid-November that 2,000 workers would be cut from the art projects alone.115 The reaction of the artists to the threatened cuts was exacerbated by comments allegedly made by FAP business administrator Elmer Englehorn, who at a forum to discuss the future of the federal art projects, told the crowd, “Let the artist dig ditches, er…let him be absorbed in other industries,” trying to relegate the vast majority of artists back to their pre-Depression jobs.116

At a rally on November 30, at a high school near Gramercy Park in Manhattan, more than 1,200 workers from various art projects across the city gathered to plan next steps and mobilize. Gorelick, a union organizer and FAP muralist, delivered a rousing speech:

117 Boris Gorelick, “The Artist Begins to Fight!” Art Front, January 1937, 5.

We say we are going to resist any and every effort by the government to take our jobs. We say that our resistance will take on such a character as to smash any efforts to institute dismissals regardless of pretext. These projects cannot be curtailed. On the contrary, they must become a permanent feature of our social and national life. From now on we are on the offensive. Our defensive is vigorous counterattack. We must intensify our activities, force the rescinding of dismissals and pink slips, the reinstatement of all fired workers, the expansion of all projects to include the millions still unemployed.117

118 Morris Neuwirth, “219!” Art Front, January 1937, 4. 119 Morris Neuwirth, “219!” Art Front, January 1937, 4; Gerald M. Monroe, “Artists as Militant Trade Union Workers During the Great Depression,” Archives of American Art Journal 49, no. 1/2 (2010), 48.

Less than 24 hours later, riled up by the revolutionary spirit of the evening before, 400 union members congregated to stage a sit-in at the FAP offices on Fifth Avenue. Two hundred and twenty-five of them were successful in occupying the offices and were preparing to stay the night, as sandwiches and cups of coffee were passed around.118 Spokesman for the delegation, sculptor Paul Block, judging that the situation could escalate, preemptively placed responsibility for any potential violence on Englehorn and the rest of the WPA administrators. Telegrams were sent, via messenger boy, to Hopkins and President Roosevelt, protesting the impending cuts. Soon after, New York City police arrived with patrol wagons and tensions quickly escalated. Twelve of the artists, including Block, were beaten, and 219 were arrested, the largest mass arrest by the NYPD ever at the time.119

120 Gerald M. Monroe, “The Artists Union of New York,” Art Journal 32, no. 1 (1972), 18. 121 Max Spivak, Oral history, interview by Harlan Phillips, 1965, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution.

In the years that followed, the union continued to stage demonstrations and sit-ins to protest layoffs and increase wages. In fact, union members credited New York FAP administrator McMahon with subtly assisting them. She would drop a hint to one of her contacts in the union if she thought there was an opportunity for the union to advance one of their demands, and in return, the union would often find a way to indirectly warn her if they were planning a demonstration.120 She defended the need for the protests, as they helped her make her case to upper-level administrators that the art projects shouldn’t be cut.121

122 “The Meek Shall Inherit the Wage Cut,” Art Front, November 1935, 3; “Wages and Hours,” Art Front, December 1935, 3; “Prevailing Wages for Artists,” Art Front, September-October 1936, 3; Gerald M. Monroe, “Art Front,” Archives of American Art Journal 13, no. 3 (1973), 18. 123 “July 1st, 1936,” Art Front, February 1936, 3; Francis V. O’Connor, “The New Deal Art Projects in New York,” American Art Journal 1, no. 2 (1969), 74. 124 Francis V. O’Connor, “The New Deal Art Projects in New York,” American Art Journal 1, no. 2 (1969), 64. 125 Gerald M. Monroe, “Artists as Militant Trade Union Workers During the Great Depression,” Archives of American Art Journal 49, no. 1/2 (2010), 50. 126 “The Lag in the WPA,” Art Front, December 1935, 3; “Towards Permanent Projects,” Art Front, May 1936, 5; “Full Report of the Eastern District Convention of the Artists’ Unions,” Art Front, June 1936, 5. 127 “Organize Against Lay-Offs,” Art Front, July 1936, 3.

In many cases, the union’s actions worked. They were successful in preventing a wage cut in mid-1935, lowering the weekly working hours from 30 to 24 while maintaining the same pay in late 1935, winning an increase in the minimum wage scale in 1936, and eventually achieving the highest allowable wages in the WPA.122 Additionally, while average employment in the entire WPA decreased 11.9 percent from January to June 1937, employment on the four Arts Projects actually increased 1.1 percent. Most importantly, the FAP was slated to end on July 1, 1936, but continued to exist in some form until 1943.123 Of the $35 million in estimated expenditures over the FAP’s eight-year history, roughly 40% of it was spent in New York.124 Art historian Gerald Monroe attributes “the exceptional working conditions, the unusually large percentage of the national quota granted to the New York City art project, and the generous exceptions to the usually stringent relief requirements” to the pressure and organization of the Artists Union.125

Of course, artists were motivated to organize, protest, and go on strike by their own economic security, particularly when fighting for a better wage scale. But the union’s efforts to curtail FAP reductions time and time again were also driven by their staunch belief in cultural democracy, that art for every person is essential for an advanced society. Calls to make the art projects permanent or to stop administrators from trimming existing payrolls were always justified by citing the need to bring cultural activities to communities where there were none. A long-term commitment to the arts would, the union argued, maintain and advance cultural standards by endorsing a broader distribution and understanding of art in the general public.126 An article in the July-August 1936 issue of Art Front detailing the need to organize against approaching WPA cuts exemplifies the union’s commitment to a higher ideal:

Surveys presented [to WPA administrators] by the [union] delegation proved conclusively that the present projects have not been able to satisfy the cultural needs of the American people. Hundreds of thousands of adults and children have been given the opportunity to study art and art appreciation for the first time in their lives in many communities. Thousands of public buildings and parks still lack mural and sculptural decoration. Art is a natural resource of the country. It must be developed. To curtail the arts projects now is on a level with Hitler’s anti-culture campaign. Art is a living necessity for both artist and public, not a “luxury” indulged in by a few private connoisseurs.127

It’s impossible to calculate how many fewer artists would have been employed or how many fewer works would have been produced if the union had not been successful in curtailing cuts time and time again, but the efforts to make the FAP larger and longer lasting than intended meant that government-sponsored artwork found its way to nearly every corner of America.

128 Martin R. Kalfatovic, The New Deal Fine Arts Projects : A Bibliography, 1933-1992 (Metuchen, N.J. : Scarecrow Press, 1994), 441.

The union’s success in making the FAP last much longer than anyone initially intended meant that its impact actually exceeded the union’s initial vision—eventually nearly 100 art centers and galleries across the country were founded, bringing art not just to all classes of people, like the Artists Union had done in New York City, but also to those who lived far from major cities in places like Casper, Wyoming, Bradenton, Florida, and Clinton, Oklahoma.128 These centers, open to all people, organized shows of the best work created by FAP artists, held lectures, and offered art classes.

129 Francis V. O’Connor, “The New Deal Art Projects in New York,” American Art Journal 1, no. 2 (1969), 64.

In the end, the nearly 10,000 artists that had been on the FAP payroll had produced 2,566 murals, 108,099 easel paintings, 17,744 sculptures, 11,285 designs for fine prints, and 22,000 plates for the Index of American Design, a program designed to conduct a survey of the decorative art and craft styles of the United States since the early colonial period.129 The FAP’s scope was so large and its impact so great that today, the term “WPA” is mistakenly used to describe art from all four of the art projects of the New Deal, including the PWAP and Treasury Department’s Section of Painting and Sculpture, which awarded commissions based on competitions. In fact, because the FAP’s reach was so large and the project’s artists were selected based on relief rather than merit, and therefore were often less experienced and less skillful than artists on other projects, art historian Victoria Grieve credits it with the creation of “middlebrow” culture:

130 Victoria Grieve, The Federal Art Project and the Creation of Middlebrow Culture (Champaign: University of Illinois Press, 2009), 85.

First, making the arts accessible to middle-class people through regular exposure and education liberated cultural knowledge from wealth. Second, the FAP discarded the commonplace assumptions that culture required great commitments of time and effort limited to the leisured classes, that one should become familiar with only the “best” art, that cultured individuals commanded deference from those less sophisticated, and most importantly, that art should remain separate from the world of commerce.130

131 Laura Hapke, Labor’s Canvas: American Working-Class History and the WPA Art of the 1930s (Cambridge Scholars Publishing, 2009), 53. 132 “Revolutionary Art at the John Reed Club,” Art Front, January 1935, 6.

But what about the work itself? The only requirement from the government was that any FAP art should depict an “American scene,” a stipulation that offered artists broad creative license. Many artists focused on depictions of industrial workers, whose efforts to build machines and repair infrastructure were “emblematic of the strengthened nation” that the New Deal hoped to create.131 While many Artist Union members were part of that trend, its more radical and Communist members were intent on portraying the struggle of the proletariat and glorifying the industrial worker, rather than promoting U.S. nationalism. In early 1935, the union declared that the best artists of the time have “cut themselves adrift from the Juggernaut of capitalist imperialism and have identified themselves, and consequently their art, with the working-class struggle for power.”132 These artists, working in an era when more art was being distributed to the public than ever before, helped usher in a dramatic shift in the subject matter of cultural productions and the artistic media used to create them.