CONCLUSION

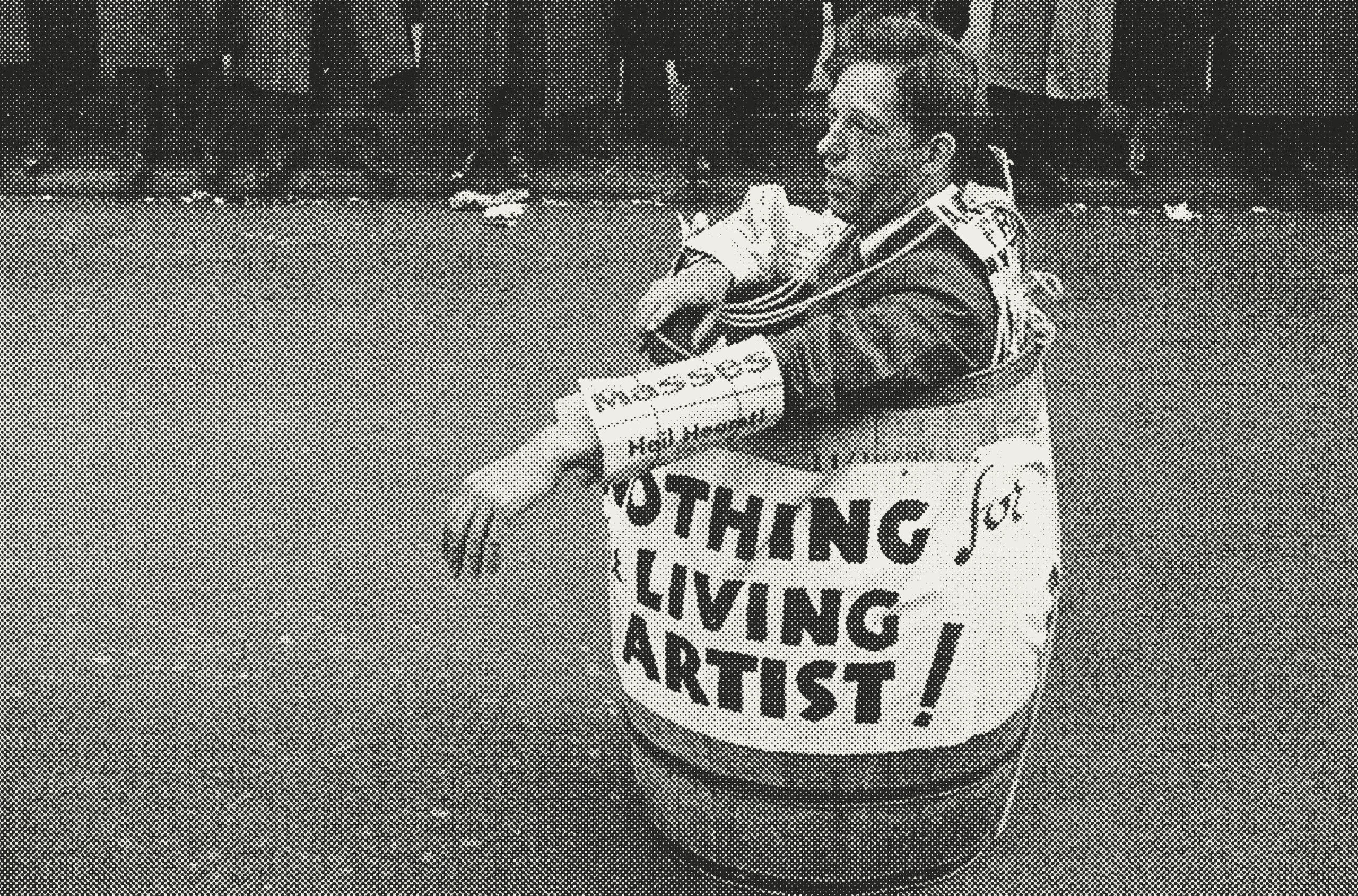

In April 1937, seeing that the economy was improving and fearful of inflation, President Roosevelt and Congress agreed to cut WPA funds by 25 percent. On Tuesday, June 27, the pink slips were handed out to 1,100 members of the New York division of Federal One. The next day, 60 workers staged a sit-in in at the payroll offices of the New York City Arts Project. Two days after that, on Friday, a group of 50 union members traveled to Washington, D.C., invaded the WPA headquarters, and demanded to see Director Hopkins. That same day, back in New York City, 600 Federal One workers occupied the offices of the New York division. Harold Stein, who had been recently appointed administrator for the New York division, was essentially held hostage as the union prevented him from exiting the offices until they were put in contact with the group in D.C. and their demands were met. Stein eventually negotiated an agreement and was allowed to leave Saturday morning, fifteen hours after the initial sit-in began. The D.C. delegation was able to meet with one of Hopkins’s assistants and walked away thinking that it had secured some concessions, but the assistant later announced that there had been a misunderstanding and reaffirmed the administration’s cuts.

Program cuts only tell half of the story of the Artists Union’s demise. The other half is a chronicle of changing leadership and organization that led to a fracturing of the group, a fate that had befallen so many radical organizations before them. Tracing the activity of the union around this time also becomes much harder. Almost overnight, without warning, the Artists Union decided to stop publishing Art Front in late 1937—the final issue, published in December, was still seeking subscriptions and contained a form to notify the union of a change in address. Even among members who were interviewed for oral histories later in life, none can pinpoint a reason why the publication stopped so abruptly, although some guessed that it was a cost-cutting measure by the union’s executive board.

155 Gerald M. Monroe, “Artists as Militant Trade Union Workers During the Great Depression,” Archives of American Art Journal 49, no. 1/2 (2010), 51.

In January 1938, trying to anchor itself to a stronger, more established labor organization, the Artists Union combined with two other small craft unions to become the United American Artists, joining the CIO-affiliated United Office and Professional Workers of America (as mentioned briefly in Chapter One). Becoming part of a more professional union, however, meant less tolerance for the radical, informal nature that had defined the union in prior years. The Greenwich Village office, with large, open lofts in which artists could socialize, was replaced with an uptown headquarters with offices and drop ceilings.155 Unhappy over the merger with a group of workers whose interests were seen to be drastically different from artists, longtime union member Stuart Davis launched a separate group called the American Artists Congress. Aimed at the most successful fine artists, the organization had its eye on advocating for the professional needs of artists outside of relief programs and took a lot of Artists Union members away from the activities of United American Artists, even if they were still nominally members.

156 Franklin Roosevelt, “Letter to the Federal Works Administrator Discontinuing the W.P.A,” December 4, 1942, The American Presidency Project.

The political appetite for cutting WPA programs did not disappear, and the story of the April 1937 cuts proved to be a template for the next several years—the union was fiercely militant and strong enough to keep the FAP intact for many years more than some politicians would have liked, but budget deficit hawks and early Red Scare witch hunts meant that the question was not if the WPA would end, but when. The program received a brief second wind during the early days of World War II making posters for the war effort, but the low wartime unemployment meant that all relief programs were eliminated entirely by the end of 1942.156

The experiment of government-funded public art that the Artists Union of New York helped enact is lasting in our collective memory, and its legacy still has impacts today. Exhibitions of FAP work routinely travel around the country to galleries and museums, and the immense body of work of the poster and graphic departments created a distinct look that is still known as “WPA style.” Permanent government patronage never came to fruition on the scale that the union imagined, although Federal One established the basis for the 1965 creation of the National Endowments for the Arts (NEA), which is still active today.

157 Peter Marks, “Arts Workers Are Building a Labor Movement to Save a Creative Economy in Peril,” Washington Post, January 8, 2021.

Today, nearly a century after the Great Depression, the COVID-19 pandemic caused many of the same financial hardships and revealed similar systemic issues for creative workers, whose jobs, especially in entertainment, vanished when the country went into lockdown. According to Washington Post critic Peter Marks, there is a prevailing sense that art has become seen as a luxury once again, evidenced by the measly $162 million allotted annually to the NEA—0.004 percent of the federal budget.157 In a “creative economy” estimated to contribute $1.7 trillion to the U.S. GDP, artists are once again aiming to change the perception that art is only for the rich, with multiple nonprofits popping up to advocate for artists and secure government assistance. “Just by adding the word ‘worker’ to a regular rank-and-file artist, we hope that that gives artists more of a sense of identity as labor, and that the art they create is worthy of a living wage,” said actor Carson Elrod, almost as if he was reading from an issue of Art Front. Hell, they’ve got to eat, too.