INTRODUCTION

As the Covid-19 pandemic stretches into its second year and second presidential administration, many commentators and academics have drawn comparisons to another national crisis that, without significant government intervention, would have dragged on for years longer and caused even more hardship and suffering: the Great Depression. In fact, pundits and public intellectuals are likening newly inaugurated President Joe Biden’s agenda to President Franklin Roosevelt’s New Deal, a massive series of work programs, stimulus packages, reforms, and regulations that provided unemployment relief, created new jobs to put Americans back to work, and helped stabilize the national economy.

1 “Emergency Relief Appropriation Act of 1935,” Pub. L. No. H.J. Res. 117 (1935). 2 Deborah Mutnick, “Toward a Twenty-First-Century Federal Writers’ Project,” College English 77, no. 2 (2014), 126; John Y. Cole, “Amassing American ‘Stuff’: The Library of Congress and the Federal Arts Projects of the 1930s,” The Quarterly Journal of the Library of Congress 40, no. 4 (1983), 366.

Before President Biden was even sworn in, New York Times cultural critic at-large Jason Farago and Carol Becker, dean of Columbia University's School of the Arts, among others, called for the twenty-first century equivalent of the New Deal program that is perhaps most lasting in our national memory: Federal Project Number One, or simply Federal One, although very few know it by either name. The five divisions of Federal One—the Federal Art Project, Federal Music Project, Federal Theatre Project, Federal Writers' Project, and the Historical Records Survey—organized under the Works Progress Administration (WPA), were responsible for some of the most important cultural projects of the twentieth century. Allocated $27 million in total funding, the equivalent of over half a billion in 2021 dollars, these programs funded the now-famous work of writers, artists, and photographers like Zora Neale Hurston, John Steinbeck, Jackson Pollock, and Dorothea Lange.1 Perhaps more importantly, the programs also established community art and music centers, preserved cultural artifacts and narratives from the last living generation of enslaved people, and researched and catalogued historical records. At its peak, Federal One was responsible for the employment of 40,000 artists, musicians, actors, and writers, producing cultural material that “reflected a sense of rediscovery of America’s cultural heritage” as part of “a renewed search for national traditions during a troubled decade.”2

3 Victoria Grieve, The Federal Art Project and the Creation of Middlebrow Culture (Champaign: University of Illinois Press, 2009), 3.

Such a large, comprehensive, and well-funded relief program seems nearly impossible in the modern era of partisan gridlock, neoliberal ideological hegemony, and constant budget deficit concern trolling, even in the midst of a massive crisis. But its passage was hardly guaranteed during the Great Depression, either. While the early years of the Depression are infamously marked by President Herbert Hoover’s reluctance to introduce large-scale federal relief programs, the economy did not immediately improve when Roosevelt took office in 1933. Although Roosevelt’s critics portray him as a bleeding-heart government spendthrift, his initial New Deal work relief programs were quite paltry overall, and virtually nonexistent for artists.3 At the time, artists were almost entirely reliant on private patronage to make a living and suffered greatly as the U.S. economy tanked and the willingness of private individuals to spend money to create and support art vanished.

FORMATION and INITIAL ORGANIZATION

In the summer of 1933, at the nadir of the country’s economic collapse, when nearly one in four Americans was out of work, around two dozen unemployed artists began meeting at the John Reed Club, which. since its founding in the wake of Black Tuesday four years prior, had become the de facto space for writers, artists, and other creative minds aligned with Marxist and leftist political ideology. Taking inspiration from the Diego Rivera, David Alfaro Siqueiros, and the Syndicate of Technical Workers, Painters, and Sculptors, a Mexican artists group that had organized to attain commissions from the Mexican government following that country’s revolution a decade earlier, the artists issued a manifesto demanding that the state fund art projects, both to provide economic assistance to artists and cultural service to the greater community. They called themselves the Unemployed Artists Group (UAG).

4 William W. Bremer, “Along the ‘American Way’: The New Deal’s Work Relief Programs for the Unemployed,” The Journal of American History 62, no. 3 (1975), 642. 5 Gerald M. Monroe, “The Artists Union of New York,” Art Journal 32, no. 1 (1972), 17. 6 “History of the Artists Union,” Art Front, November 1934, 4. For the sake of simplicity, individual articles from Art Front do not appear in the bibliography, but the entire online archive of copies of Art Front from which all articles are sourced is cited as “Digital Archive of Art Front.” 7 Matthew Spender, From a High Place: A Life of Arshile Gorky (University of California Press, 2000), 115. 8 “Idle Artists March in Protest on CWA; 100 Demonstrate in Front of Mrs. Force’s Offices, Charging Unfairness in Giving Jobs,” The New York Times, January 10, 1934, sec. Art-Books, 19.

Despite the attention the manifesto received in creative circles, when the first large-scale jobs program of the New Deal, the Civil Works Administration (CWA), was unveiled in November 1933, it did not include any positions or programs for artists.4 The acclaim that the group’s summer manifesto received among artists desperate for work meant that the UAG, now some 300 strong, was quickly able to develop a petition specifically outlining their demands for the creation of federally-funded mural painting, easel painting, commercial art, and art teaching jobs.5 The UAG’s efforts to organize and unite New York City artists were successful: by late December 1933, Harry Hopkins, the head of the CWA, established the Public Works of Art Project (PWAP), incorporating parts of the petition.6

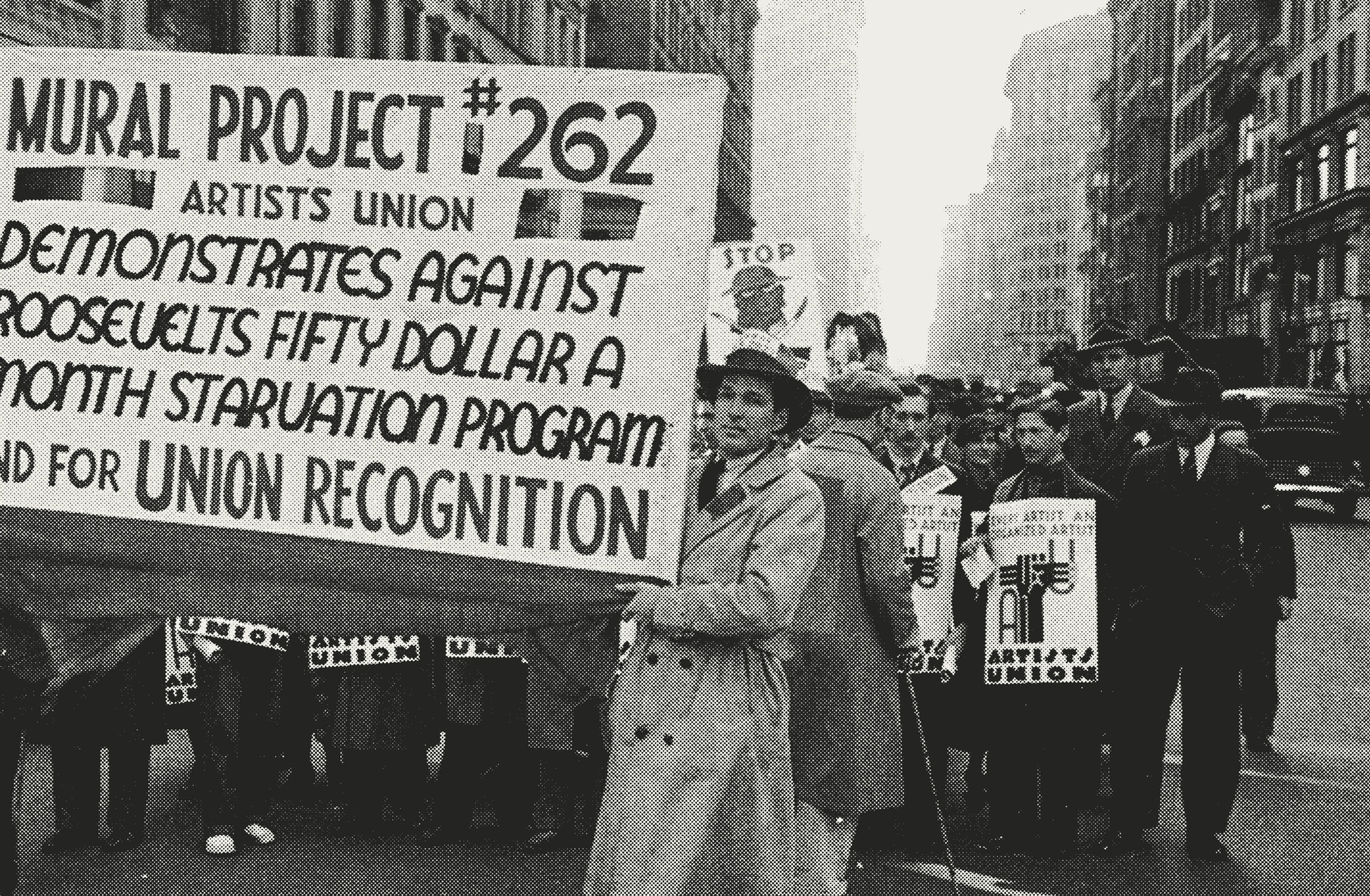

However, as job appointments were delegated to local administrators, the artists of the UAG were shut out of New York City positions. Juliana Force, the director of the Whitney Museum and close friend of the Vanderbilt family, had been appointed administrator of the PWAP for the New York region and scorned the group’s politics.7 Leaning into their reputation as radical troublemakers, the UAG artists arranged a demonstration at the Whitney. On January 9, 1934, more than 100 artists gathered at Washington Square Park to march to the museum around the block, carrying banners and picket signs that read “Art Work for Needy Artists or Immediate Cash Relief” and “The Word Need Is Not in My Vocabulary,” an ironic reference to a comment by Force at an earlier conference of administrators arguing that relief should be merit-based. The protests continued for several weeks despite often being broken up by police. On one occasion, after being forced back to Washington Square, UAG members returned, arms either interlocked with other members or outstretched to offer a taunting wave to Force in her office above.8

9 “History of the Artists Union,” Art Front, November 1934, 4.

Tired of the harassment, Force capitulated soon after and many UAG members were offered work. Given that a considerable amount of the Unemployed Artists Group were now employed, the members agreed to change the name to the Artists Union.9

10 Jerry Adler, “1934: The Art of the New Deal,” Smithsonian Magazine, June 2009. 11 “For a Federal Permanent Art Project,” Art Front, November 1934, 4. 12 “For a Federal Permanent Art Project,” Art Front, November 1934, 4. 13 Stuart Davis, “The Artist Today: The Standpoint of the Artists’ Union,” The American Magazine of Art 28, no. 8 (1935), 476.

The PWAP was still woefully underfunded and drew considerable criticism from the Artists Union. The program only ran for less than six months and employed a meager 3,700 artists across the country.10 In New York City, only 700 out of 4,000 applicants found a place in the program, but even they were “juggled on and off the payroll…faced with the same disregard and brutal callousness which characterized the [Roosevelt] Administration prior to the PWAP.”11 State and municipal level programs, first chartered during the Hoover years of federal inaction, drew similar ire. The New York State Relief Administration paid wages less than two-thirds that of the federal programs, and artists were hired only after successfully navigating degrading competency tests and red tape, sometimes waiting up to ten weeks to receive a response.12 As painter Stuart Davis concluded in the 1935 issue of the American Magazine of Art, “The artist today is in a state of confusion, doubt, and struggle.”13

14 Gerald M. Monroe, “The Artists Union of New York,” Art Journal 32, no. 1 (1972), 17.

By late 1934, the Artists Union had become established as the primary advocate for New York City artists seeking relief and had ballooned to over a thousand members, routinely getting two to three hundred members at their weekly Wednesday night meetings. “If there was a community of artists in New York City, then the Union was its place of congregation,” historian Gerald Monroe remarked.14 The union’s campaign evolved into demands for a permanent federal art project—the Artists Union not only viewed government patronage as a remedy to the miserable economic conditions, but also as a lasting fix to the system of private patronage that they saw as fickle, unfair, and exploitative.

15 Matthew Spender, From a High Place: A Life of Arshile Gorky (University of California Press, 2000), 115.

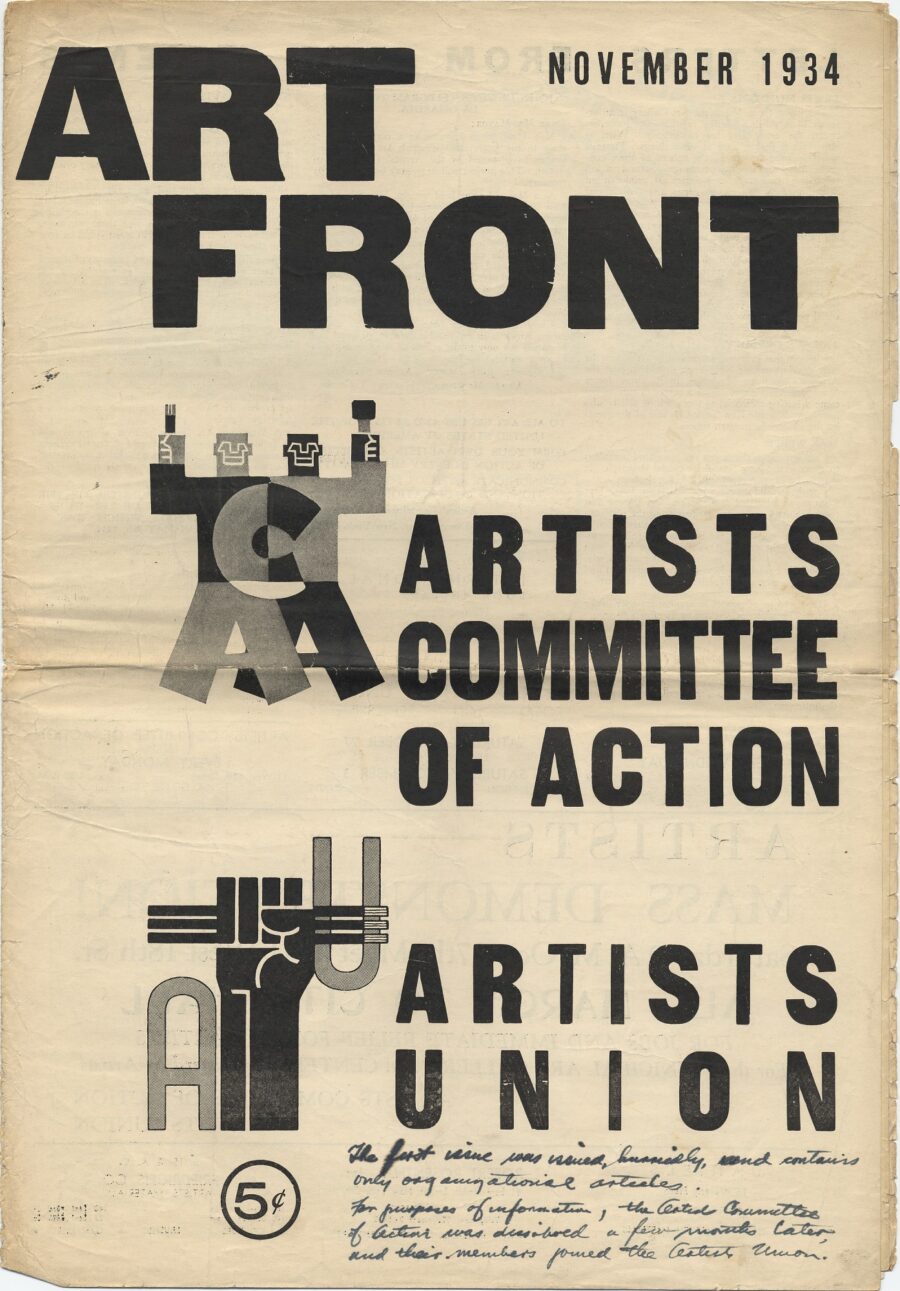

To further broadcast its message and organize hundreds of members to fight for permanent, adequate federal relief for all artists, the Artists Union began producing a monthly magazine called Art Front in November 1934; the title alluding both to the Communist Party USA (CPUSA) Popular Front strategy against fascism and the union’s goal to push the boundaries of contemporary art. The magazine was co-published with the Artists Committee of Action, a small group of artists who had formed to protest Nelson Rockefeller’s decision to destroy Diego Rivera’s Man at the Crossroads mural because it portrayed Lenin, although that organization doesn’t appear on the masthead of later issues and was later absorbed by the union.15

16 Art Front, November 1934, 2. 17 Virginia Hagelstein Marquardt, “Art on the Political Front in America: From The Liberator to Art Front,” Art Journal 52, no. 1 (1993), 78.

In its first issue, the union declared that “the scope of the magazine will be as wide as art is itself.”16 Staying true to its promise, Art Front, which was published monthly, included a wide variety of written and visual content, including letters to the editor, policy demands, illustrations, news on strikes and protests, and criticism and reviews of art shows and museum exhibits. During its three years of publication, Art Front became “the single most important forum for radical and nonradical artists to air their views concerning the appropriate social function of art, to review and address new art movements, and to lobby for federal support,” according to art historian Virginia Hagelstein Marquardt.17 Art Front served as a clearinghouse for critiques of art and society by artists who had significant ties to leftism and Communism, and in its pages, we can trace the influence that the Artists Union wielded far beyond the New York art world. In this thesis, I argue that artists involved in the Artists Union, through their work in the Federal Art Project, redefined conceptions of artists, disrupted American norms about public art, and pioneered new forms and content in fine art.

FINDING ART FRONT & the ARTISTS UNION

I first found Art Front in the early stages of the thesis process, when I was looking for ways to explore the intersections of visual culture and organized labor. Initially, I wanted to study specific artistic techniques and technologies, such as silk screening, to examine how their ability to create printed work rapidly and disseminate information might have impacted unions as they attempted to organize, bargain, and strike. An online search for both “art” and “organized labor” quickly led me to the Artists Union and naturally then to Art Front.

While the Artists Union and Art Front have been popular topics among researchers for several decades and have been the subject of a good deal of existing scholarly research, that work is largely contained to the union or the magazine itself and does not examine the impact that they had on actual artists’ work or broader trends and attitudes. Most of the existing scholarship focuses on strictly historical narratives of the Artists Union and related organized labor movements that may reference artists; analysis of the visual culture of organized labor broadly; criticisms and analysis of contributions by specific artists during the WPA era without reference to the labor movement; or connections between leftist or Communist ideology and the work produced during the time, but without examination of specific productions or broader effects on culture.

18 Gerald M. Monroe, “Artists as Militant Trade Union Workers During the Great Depression,” Archives of American Art Journal 49, no. 1/2 (2010), 45.

Patricia Hills and Gerald Monroe are the leading scholars of the specific historical narratives about the Artists Union and other artist labor movements of the same time and have authored several works on the Union. Monroe’s 1974 article “Artists as Militant Trade Union Workers During the Great Depression,” for which Hills wrote the introduction when it was rereleased in 2010, details the realization of artists that, during the Great Depression, their “economic and professional needs could only be obtained through massive government patronage.”18 He traces the activity of Max Spivak, Phil Bard, Boris Gorelik, and other New York artists and their journey to create the union, how the union became an influential social force in the New York art scene, and the union’s battles with administrators of museums, such as the Whitney, for better pay and bargaining rights. My work certainly relies heavily on theirs for context and insight but seeks to go beyond it by connecting the ideology of the Artist’s Union and Art Front to the work of artists involved in the union and their broader cultural impact.

19 John Ott, “Graphic Consciousness: The Visual Cultures of Integrated Industrial Unions at Midcentury,” American Quarterly 66, no. 4 (2014), 884.

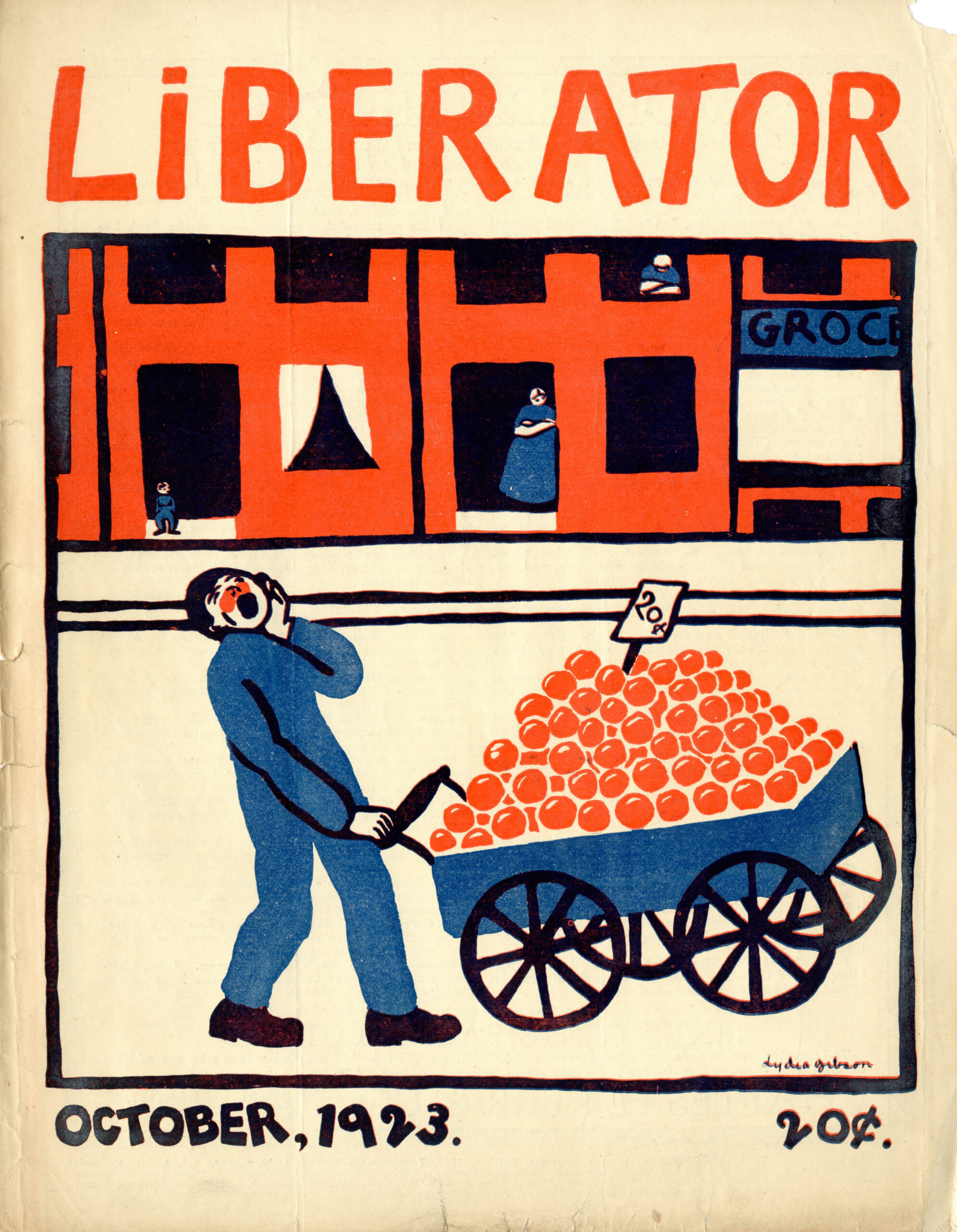

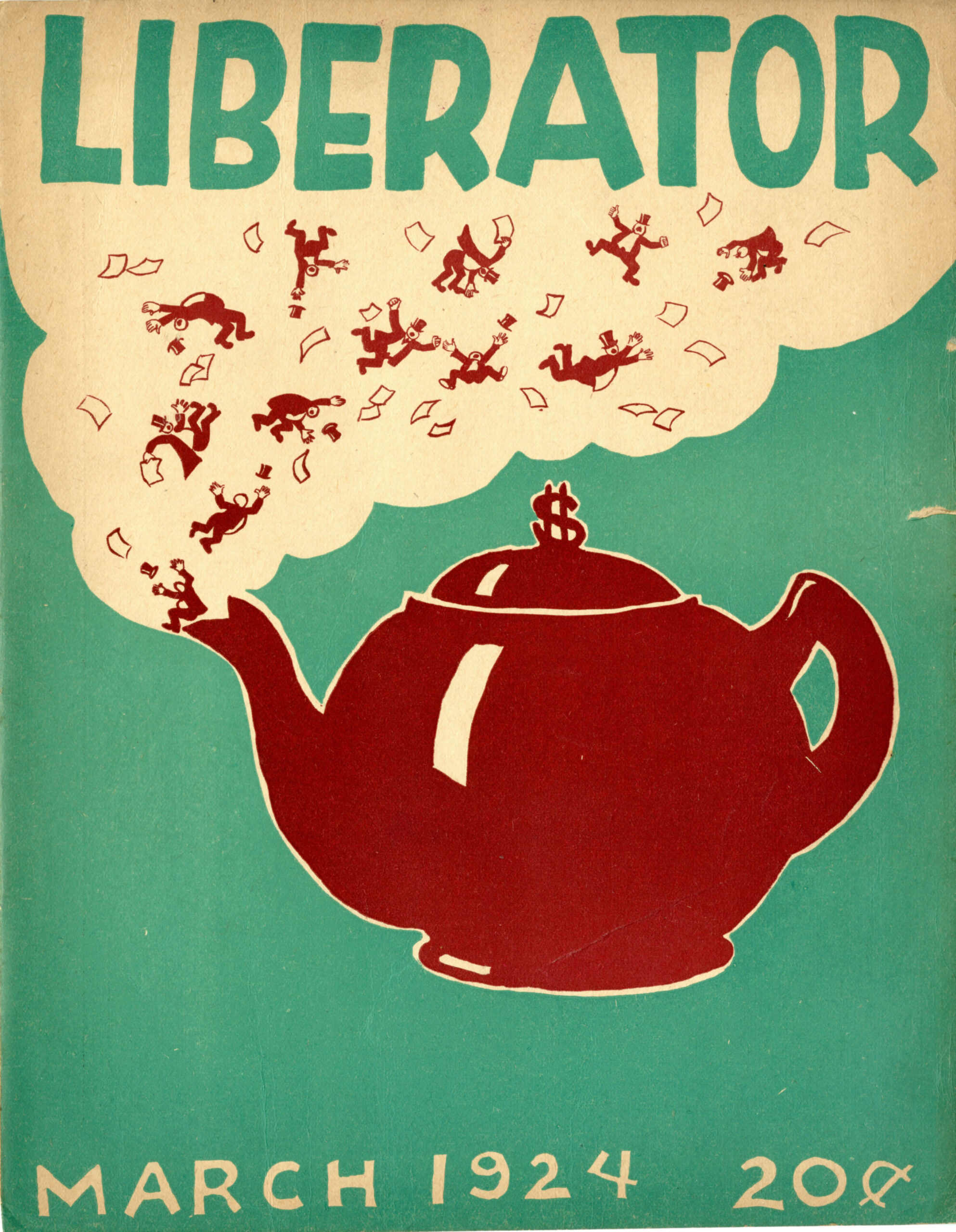

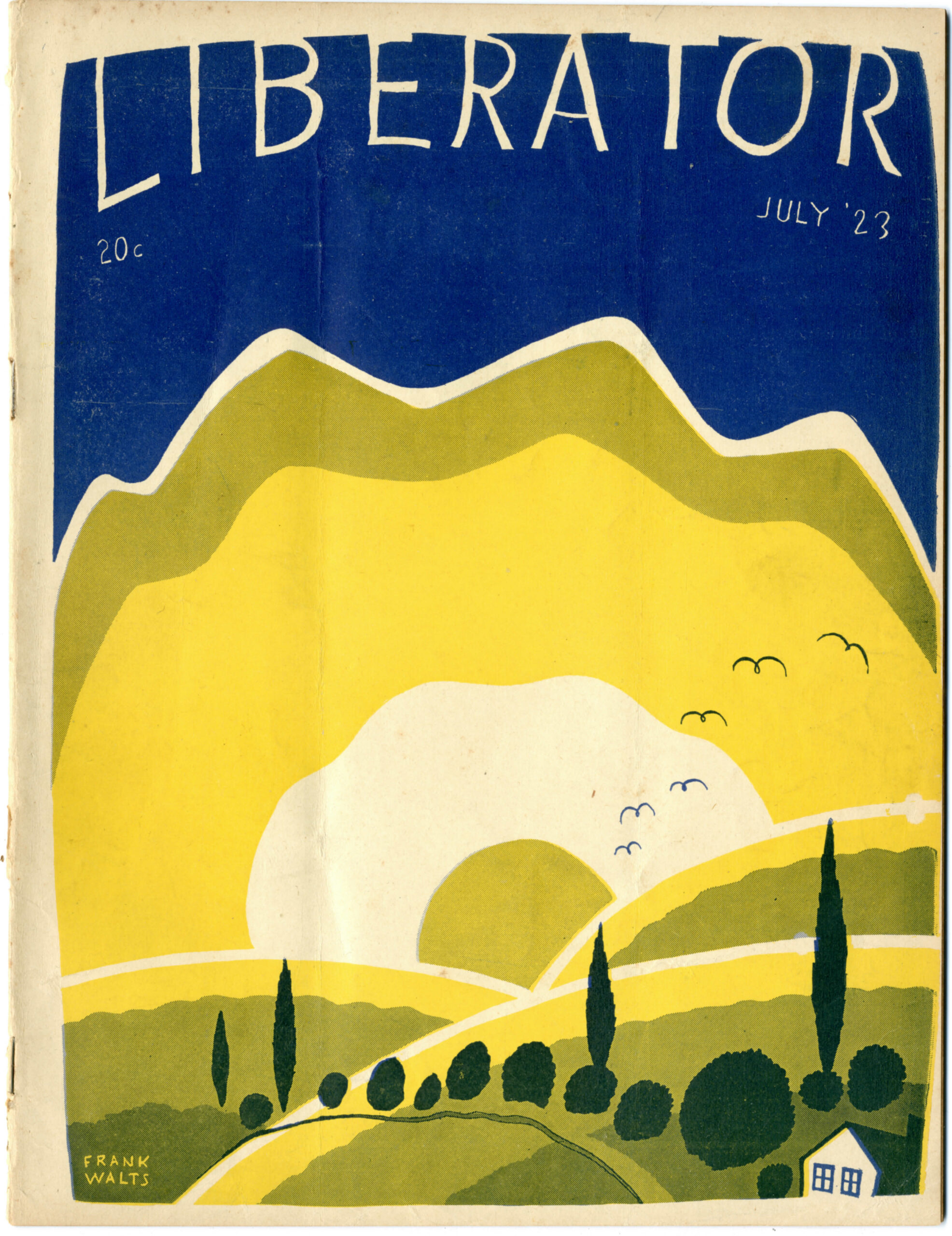

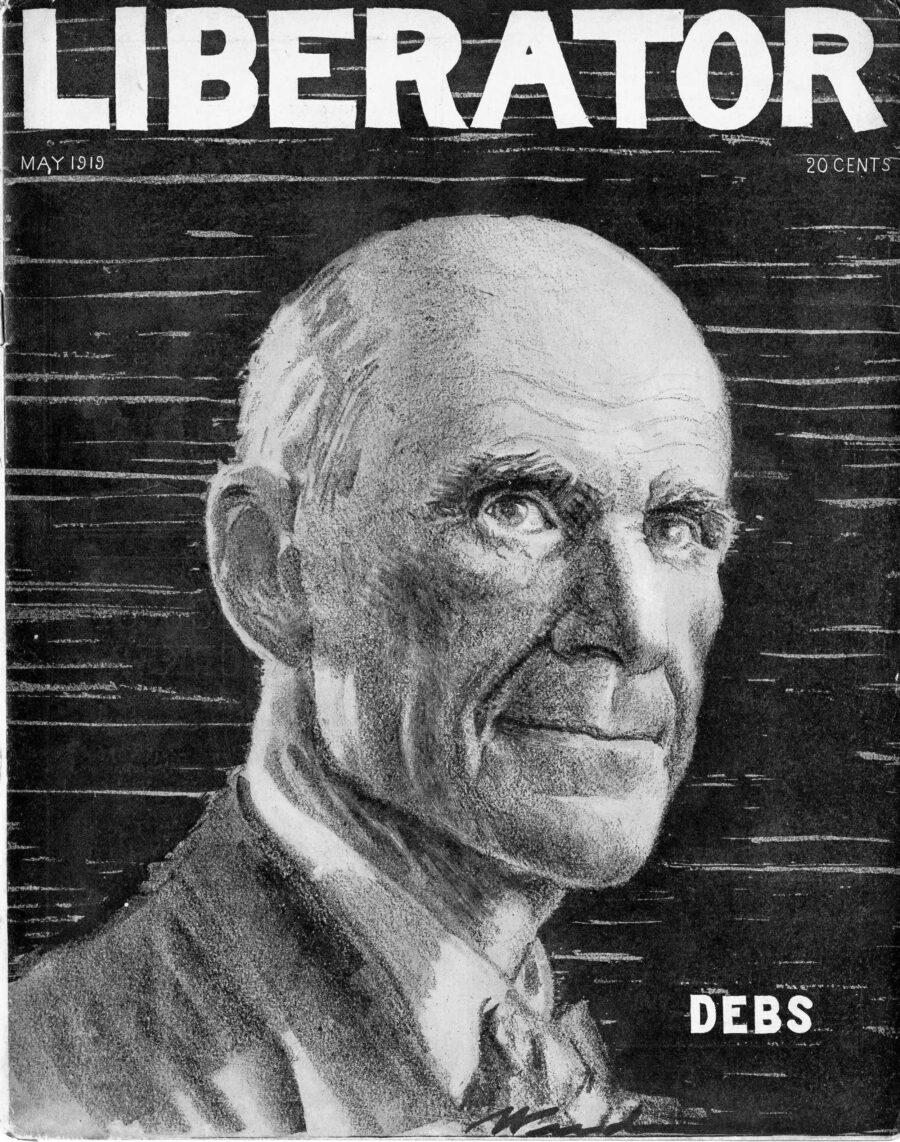

In his work on the importance of examining “low” artwork that is normally excluded from scholarly analysis, such as labor pamphlets and periodicals, art historian John Ott discusses the role of artists’ organizations within the broader labor movement. His 2014 article “Graphic Consciousness: The Visual Cultures of Integrated Industrial Unions at Midcentury” argues that art historians should go beyond “conventional salon painting and sculpture” and examine vernacular art produced for (and by) a blue-collar audience.19 In particular, he offers an interesting critique of organizations like the John Reed Clubs, the precursor to the Artists Union and American Artist’s Congress, arguing that even their organized labor movements were channeled back towards patronage of salon painting and other high art, suggesting that there might have been a disconnect between the union activity of artists and blue-collar workers. Adding in-depth analysis to the publications of several of the groups discussed by Ott, Virginia Marquardt’s “Art on the Political Front in America: From The Liberator to Art Front” traces the way leftism and political ideology found its way into art during the early twentieth century by focusing on artist-made magazines, including Art Front. Marquardt offers both a helpful model for analyzing social and political commentary in visual art and helpful historical context for the precursors to many of the Depression-era labor movements.

20 Jane De Hart Mathews, “Arts and the People: The New Deal Quest for a Cultural Democracy,” The Journal of American History 62, no. 2 (1975), 337.

The work of art historian Jane De Hart Mathews is particularly relevant to the latter parts of my research, in which I link my analyses of Art Front and WPA cultural productions to popular American attitudes towards art at the time. Her article “Arts and the People: The New Deal Quest for a Cultural Democracy,” examines how the administrators and directors of the New Deal attempted to “integrate the artist into the mainstream of American life” and informs my conclusions about the connection between people’s newly expanded access to art and the messages and ideology that the art was conveying, and how that might speak to larger sociopolitical trends or attitudes.20

Finally, professor of working-class studies and labor literature Laura Hapke’s book Labor’s Canvas: American Working-Class History and the WPA Art of the 1930s studies the workers and labor represented the work created in the Federal Art Project (FAP) under the aegis of the WPA. My thesis attempts to connect the political ideology of the Artists Union and Art Front with the actual work produced during the FAP, building on Hapke’s analysis and relying on her previous curatorial work of gathering a huge archive of paintings and prints.

The work of these scholars was crucial for building the context of my project and helping me understand the narrative history of many of the important figures in the art scene of 1930s New York City. I set out to build on these existing historical accounts of the Artists’ Union by examining connections between the activity and ideology of the union (shown through issues of Art Front) and the actual art that union artists produced for the WPA, which had a much larger scope and audience. In this way, I hoped to be better able to draw conclusions on the effect of the Artists’ Union on broader American culture. This led me to my research question: How did the actions and ideology of the Artists Union, as evidenced by the written and visual content of Art Front magazine, impact the work that was produced as part of the Federal Art Project and therefore contemporary attitudes towards art and organized labor?

I started my research with close readings of the copies of Art Front that I could find online (due to COVID limitations on accessing in-person archives). Luckily, all but two issues were available as scanned PDF documents in relatively good quality. I looked for recurring themes, topics, and keywords, tone, references to other artists, and general types of content, as well as change in the magazine over the three years that it was in production. I noticed the magazine routinely adopted a systemic criticism of the art world, which it saw as dominated by private patronage and unfair to artists. As I noticed this theme, I began to note implicit or explicit references to capitalism, socialism, communism, or related terms, and saw that the magazine consistently espoused leftist ideology. There is an inherent tension in the relationship of artists who publicly espouse Communist ideas and the U.S. federal government that employed them to produce public works of art, and that conflict really interested me and focused my research.

After working my way through all of the available issues of Art Front, making sure to note the artists involved with the production of the magazine and those mentioned most often, I turned to secondary sources to help contextualize those references and help find connections between the union and the WPA—potentially looking for a few case studies of specific artists that could demonstrate clear links.

Ironically, during this research, I found examples of artists in the Artists Union that were also heavily involved in the WPA screen printing program in New York City, which is cited as one of the reasons screen printing as a technique became so popular. So, in a way, my research has partially routed me back around to my initial idea.

CHAPTER OVERVIEW

My thesis is organized into three chapters that cover four components of my claim that the Artists Union changed American expectations and norms about the status of art and manual labor in society. The first chapter begins with a discussion of the cultural and labor organizations and publications that preceded the Artists Union and Art Front, tracing how their members, many of whom who later joined the union, began to form close ties between the artistic community and the labor movement. I demonstrate that the union closely aligned artists with other working-class laborers and redefined the artist as a worker. The second chapter explores two components of my claim—the first is how the union pushed back against private patronage as the dominant system in the American art world and worked to transform the public perception of art from a rarity that was only in the purview of the rich into a public good that everyone could enjoy every day. The second is that their organization and advocacy helped establish many public art projects, including the Federal Art Project, which the union helped to ensure was quite large. As a result, it produced significant amounts of work that was seen by ordinary people across the country. The final chapter draws a connection between the union’s ideology and the artwork of its members, using a small group of union screenprinters as a case study to show how, for the first time in American history, union artists glorified workers in government-funded art that pioneered new artistic techniques.

NOTES on FORM, PROCESS, and AUDIENCE

My inspiration for the form of my final project came through the research itself. The primary historical sources for tracing the activity of the Artists Union and the organizations that led to it were art and labor publications. I spent hours looking through volumes of Art Front, The Liberator, New Masses, and many others, not only reading them for research, but getting to browse their beautiful covers and design. So, what better way to present a thesis about these magazines than to make one myself?

My final thesis project is a sort of hybrid between a traditional and non-traditional thesis that is most similar to a long-form piece of journalistic writing. The main component of the thesis is still written, but it is designed as an editorial publication. This pays homage to the rich history of these magazines but allows me to integrate written analysis and visual content in a more fluid and cohesive way that will help bolster my argument to the reader, especially because so much of my topic relies on artwork.

21 Scott Anderson, “Fractured Lands: How the Arab World Came Apart (Published 2016),” The New York Times, August 10, 2016, sec. Magazine. 22 “How to Save the Earth: Biggest Solutions for Climate Change | Time,” accessed December 3, 2020. 23 Nathaniel Rich, “Losing Earth: The Decade We Almost Stopped Climate Change (Published 2018),” The New York Times, August 1, 2018.

The closest example to my project is the August 14, 2016 issue of the New York Times Magazine that was entirely devoted to a single story by journalist Scott Anderson. The issue explains how, starting with the invasion of Iraq in 2003, the Arab world has fractured in the twenty-first century.21 The project, both in print and online, combines a serious piece of investigative journalism with dynamic typography and powerful images that help to tell the story. In the same vein, while not a single article, Time recently dedicated an entire issue to a single topic: climate change, with a unified graphic style and visual language to make the issue feel cohesive.22 The New York Times Magazine published a similar issue in 2018, which was almost entirely taken up by one story by Nathaniel Rich on the decade during which we could have taken serious action on climate change.23 In my thesis, the written parts of each chapter are interspersed with visual content—whether photographs of union activities, pieces of artwork, or contextual images—some with text wrapped around them and some on full-page spreads.

I began the design process around the same time that I began writing, using the research I had done during the first semester of the thesis process to gather photographs and other relevant visual content. I also took time to examine particularly the look and feel of the magazines I was studying, taking time along the way to look up the techniques and printing methods available to publications at the time. Over spring break, while I was taking a break from writing, I started to hone in on the particular visual language that I wanted to use—certainly inspired by the pages of Art Front, but with a modern update to avoid a dated feel and to inject some creativity into the project.

My goal for the form of the “hybrid” thesis was also to make the project more accessible to the public, using the combination of written and visual content used by countless popular publications to let the audience to see the connections and arguments I’m trying to make in a compelling way. Having nearly a decade of design experience, a third of which has been in a professional environment, approaching how to combine writing and images was relatively easy, and I didn’t encounter any significant issues.

24 Philip J. Deloria and Alexander I. Olson, American Studies: A User’s Guide (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2017), 259.

The form of the project is only part of the way in which a public piece differs from an academic work. The other is voice, which was the biggest hurdle of my thesis process: making sure that my writing was clear, concise, and would be comprehensible to a non-scholarly audience. Not only was this my longest piece of writing, but the project was my first experience with writing a public-facing piece. The single biggest help in this process was the method of “beats and stepbacks” to synthesize storytelling and analytical argument in a compelling, accessible way.24

My thesis project, at least initially, will be available as an PDF. I am planning later to have the project printed to imitate an actual publication more closely, and I may also create a website to further showcase the work.