CHAPTER ONE

EARLY DAYS

& ARTISTS

as WORKERS

On August 31, 1934, house painter John Smiuske had the day off. He chose to spend it at the Westchester Institute of Fine Arts in Tarrytown, New York, a suburb of the city that sits on the eastern bank of the Hudson River. He wanted to see the mural A Nightmare of 1934, a satirical work that criticized the Roosevelt administration and its response to the New Deal. He paid his 25-cent entry fee, and among the housewives and other gallery visitors, he calmly took out a bottle of varnish remover and doused the painting. In a quick motion, he tore the large canvas off of the wall and swiftly lit a match, igniting the mural that lay in a soaked heap on the floor. While the flames were quickly put out, the painting was ruined and Smiuske was arrested on the spot. During the investigation, it was revealed that he was enraged by the inclusion of Eleanor Roosevelt and her children as caricatures in the controversial scene.

25 “Artists Assail Lie for Aiding Vandal,” The New York Times, October 10, 1934. 26 “Jonas Lie and Property Rights,” Art Front, November 1934, 3.

What would have been a noteworthy but historically irrelevant act of a deranged man was elevated when the president of the National Academy of Design, Jonas Lie, paid the man’s $500 bail. Lie, a Norwegian-born painter who counted the First Family as close friends, apparently had similar distaste for the painting, later explaining that he was “opposed to the destruction of other people’s property…on the other hand, this overt act was committed in passion and motivated by a high ideal, therefore I sympathize with [the vandal] in his act.”25 Lie’s defense of the painting’s destruction so enraged the Artists Union that, despite the fact that it occurred about three months before the publication of the first issue of Art Front, the incident appeared on the front page. The article was accompanied by an open letter to Jonas Lie, written by Hugo Gellert, the chairman of the Artists Committee of Action (ACA), and signed by both the ACA and the Artists Union. “You, an artist, the President of the National Academy of Design, and an important official on various governmental art-projects, seem to be in accord with the aims and methods of Adolph Hitler,” Gellert wrote. “We…tolerate no bigoted, self-appointed art dictator. We tolerate no censorship.” The letter, which denounced Lie as an enemy of art and artists, called for his resignation from the National Academy of Design and his disassociation with any government projects.26

As the letter detailed, this was not the first time Lie had acted against the interests of rank-and-file artists. In February 1934, when the Artists Union and the Artists Committee of Action were protesting the decision to hold the first municipally funded art exhibition at Rockefeller Center, site of Diego Rivera’s Man at the Crossroads mural destroyed by Nelson Rockefeller, Jonas Lie arrived to scold the picketers. “The New York Times, as would be expected, sides with Mr. Lie,” raged Gellert in the letter, citing an excerpt from an editorial that praised both Lie’s painting and leadership ability and demonstrated to the union the alliance between the established art world and the bourgeoisie-owned media.

Notably, the union directed its ire solely at Lie, not Smiuske, whom they saw as a fellow worker and regarded with class solidarity. “We do not propose to punish the misguided person who destroyed that mural in the Westchester Institute,” Gellert wrote, comparing Smiuske to the much more wealthy and powerful Nelson Rockefeller, who was “never even in danger of being hauled to court” for the destruction of Man at the Crossroads. Even an enemy of art should not be jailed just for having a lower-class status and less money, he argued.

27 “Art: Poor White’s Art,” Time, September 10, 1934.

In fact, the Artists Union’s solidarity with workers and other artists—even ones who did not share their ideology—was fundamental to its protest over the destruction of A Nightmare of 1934. The mural’s artist, who painted under the pseudonym Jere Miah II, was not affiliated with the Artists Union. A spokesperson for the John Reed Club, closely affiliated with the union, explained that the muralist was certainly no radical. “The thing is full of bourgeois ideology. No radical artist would have made fun of the domestic affairs of the Roosevelt family. The fellow is a bourgeois,” he said in an interview with Time.27 In short, the Artists Union, at least in its very beginnings, was firmly committed to both solidarity with all workers and the right of artists to freely produce content of any nature, regardless of their ideological leanings, and even if they hated the work.

28 “What Now, Mr. Bruce?” Art Front, January 1935, 3; “Municipal Art Gallery,” Art Front, November 1934, 7; “History of the Artists Union,” Art Front, November 1934, 4.

Lie did not resign his position, and the incident seems to have passed without further note. But he was not alone in drawing the ire of the Artists Union. In just the first three issues of Art Front, over half a dozen elected officials and art administrators were disparaged for various perceived transgressions against the New York City art community. Notably, in an accusatory editorial titled “What Now, Mr. Bruce?” Chief Administrator of the PWAP Edward Bruce was derided for announcing a work relief plan that employed very few artists and based their commission on merit and reputation rather than need. The chair of New York City Mayor Fiorello LaGuardia’s art committee, Aida de Acosta (referred to as Mrs. Henry Breckenridge), was criticized for dragging her feet on locating a suitable building for the planned Municipal Art Center, and LaGuardia himself was denounced for cronyism in selecting sculptors who were personal friends to be on the payroll of a short-lived city art project.28

29 Bernarda Bryson Shahn, Oral history, interview by Liza Kirwin, April 29, 1983, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution; Patricia Hills, “1936: Meyer Schapiro, ‘Art Front,’ and the Popular Front,” Oxford Art Journal 17, no. 1 (1994), 30.

These public denunciations, together with the ACA and the Artists Union’s response to Jonas Lie, demonstrated a new dynamic in the New York art world that was directly influenced by Marxist principles. While not all its members were Communists, by any means, the union was largely organized by CPUSA members and was “firmly in the Communist movement,” notes art historian Patricia Hills.29 According to the Artists Union, the art world was composed of two well-defined factions that illustrated Marx’s analysis of the bourgeoisie’s exploitation of the proletariat: established art institutions and their leaders, even if they were artists themselves, were on the side of the capitalist barons and the media they owned, and were assumed to be directly opposed to the economic prosperity and artistic freedom of rank-and-file artists. Artists, on the other hand, were part of the working class.

30 Virginia Hagelstein Marquardt, “Art on the Political Front in America: From The Liberator to Art Front,” Art Journal 52, no. 1 (1993), 72.

The movement of artists who aligned themselves closely with other types of working-class jobs and emphasized themselves as workers did not begin with the Artists Union. But during its years of operation, the union highlighted this push as a central point of its argument for public work assistance, marking its transition from an ideological display of solidarity to an organizing principle. According to art historian Virginia Hagelstein Marquardt, the redefinition of artist-as-worker began in the wake of World War I.30 In 1918, The Liberator was founded by former editors of The Masses, a socialist magazine published from 1911 to 1917, when it was forced to shut down for violating the wartime mail regulations, namely conspiring to impede conscription. While The Masses was almost exclusively focused on news and written work—with the occasional cartoon—The Liberator looked to incorporate art and art criticism as a more central focus.

31 Virginia Hagelstein Marquardt, “Art on the Political Front in America: From The Liberator to Art Front,” Art Journal 52, no. 1 (1993), 73. 32 Boardman Robinson, “A Letter from Boardman Robinson,” Liberator, July 1922, 29. 33 Irwin Granich, “Towards Proletarian Art,” The Liberator, February 1921.

Although not explicitly political on matters of artistic expression, The Liberator focused on artists looking to cultivate an “indigenous” American art—indigenous used to refer to a style that did not come from the European masters, not to Native American art. That style later evolved into the concept of proletarian art, defined by its “implicitly unschooled and working-class origins,” with explicitly political messages.31 As painter Boardman Robinson wrote in the July 1922 issue of The Liberator, “‘Should the artist be a propagandist?’ I don’t think there is any ‘should’ about it. Everyone is a partisan and to some extent a propagandist of what he likes.…The very conditions of his craft make him criticize whatever he looks upon.”32 Another editor, writer Michael Gold (still writing at this time under the name Irwin Granich), asserted that a true American art could only arise from the working class, identifying Walt Whitman as the “spiritual grandfather” of the movement.33

34 V.I Lenin, “Our Party’s Press and Literature,” Workers Monthly, April 1926.

In 1924, The Liberator merged with two other labor magazines, The Young Worker and the Labor Herald, to become Workers Monthly. With this change, the magazine became an official imprint of the CPUSA, becoming decidedly partisan in its editorial slant. The publication donned the subtitle “A Communist Magazine,” embracing Lenin’s platform of “no more ‘non-party’ writers.”34 The shift in editorial focus brought a decrease in visual content overall, but small spot illustrations and cartoons still appeared around every half a dozen pages.

35 J. Louis Engdahl, “Build for the Third Year,” Workers Monthly, January 1926, 137.

Nonetheless, Workers Monthly still affirmed the cause of identifying writers and artists as workers. In a 1926 article, journalist J. Louis Engdahl wrote on the importance of a strong, Communist-aligned press, composed of journalists and artists from the working class. “An intelligent, quick-witted Communist worker, with a little experience, becomes a more skilled reporter than can be obtained among the ‘professionals’ of long training under millionaire employees or university schools of journalism,” he wrote. Later, when acknowledging some of the various artistic contributors to Communist publications, Engdahl proclaimed, “It is safe to say that one comrade, Fred Ellis, a man who works day in and day out on the scaffold as a sign painter, is a cartoonist of such truly great genius as to be compared with the greatest of the world. Then the drawings of K. A. Suvanto, (K. A. S.), O. R. Zimmerman (O. Zim), Hay Bales, Lydia Gibson, G. Piccoli, Juanita Preval, and others, show that among the ranks of the proletariat is all of the genius that is needed to make the revolutionary press.”35 Although they did not yet consider professional artists to be workers, Engdahl and Workers Monthly were making the important step of identifying and fostering artists and creative minds that were already part of the working class.

36 Virginia Hagelstein Marquardt, “Art on the Political Front in America: From The Liberator to Art Front,” Art Journal 52, no. 1 (1993), 75.

Although likely of the same political view of the rest of the staff of Workers Monthly, and probably of Lenin himself, the former editors of The Liberator soon tired of its constraints and wanted to create a publication that was free of official ideological affiliation. Moreover, they wanted a magazine committed to the development of a uniquely American culture that centered workers, having observed the principal focus of Workers Monthly evolve into solely political theory and praxis—the magazine was later renamed The Communist: A Magazine of the Theory and Practice of Marxism-Leninism.36 In the prospectus for a new magazine to be titled New Masses, the editors outlined their aims:

37 “Prospectus for Dynamo” in Virginia Hagelstein Marquardt, “Art on the Political Front in America: From The Liberator to Art Front,” Art Journal 52, no. 1 (1993), 75.

“The publication will represent no special school of literature or art and will welcome the expressions of all schools....It will regularly interpret the activities of workers, farmers, strikers, etc., but in such a way as to bring out the general human and cultural significance of particular movements. For it believes that a deeply human interpretation of any event is better than propaganda....It must strike its roots strongly into American reality.”37

38 Prospectus for Dynamo” in Virginia Hagelstein Marquardt, “Art on the Political Front in America: From The Liberator to Art Front,” Art Journal 52, no. 1 (1993), 75. 39 “In This Issue,” New Masses, December 1931, 31; “In This Issue,” New Masses, June 1930, 22; “In This Issue,” New Masses, January 1931, 23.

Predicting the creation of a dedicated artists magazine less than a decade later, the organizers of New Masses also committed at least half of the pages to only cartoons, drawings, and pictures that have “no ‘journalistic’ value but are based on the emotion of art” and appointed a stand-alone art editor.38

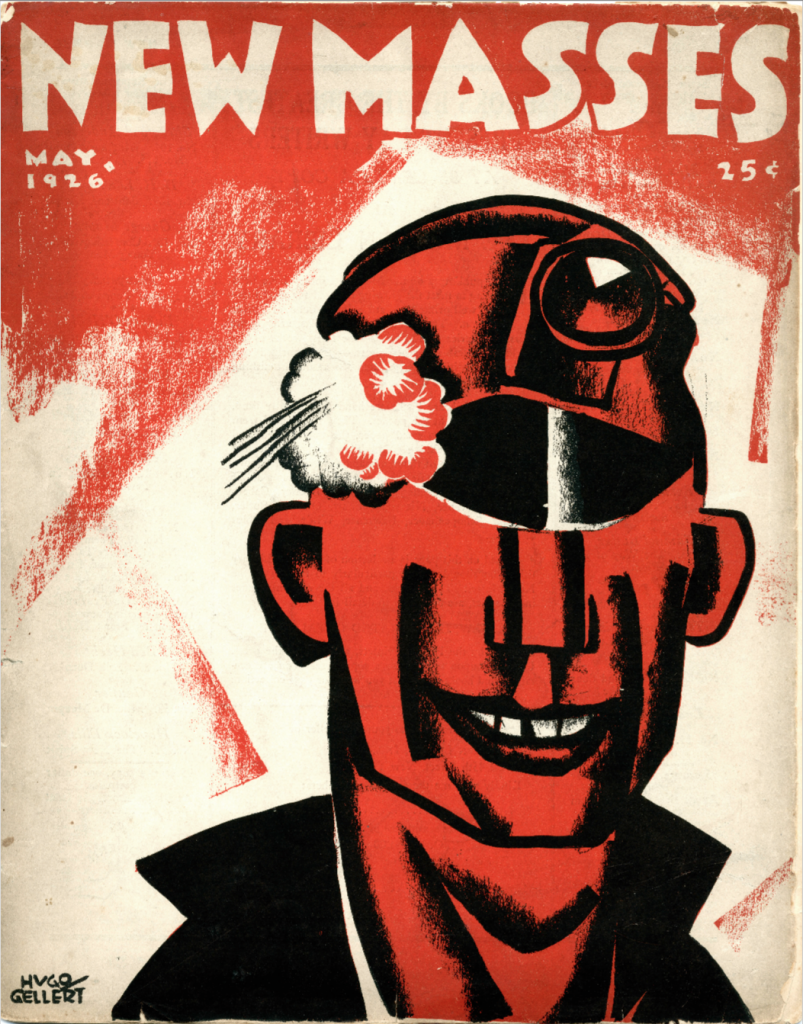

At the same time as it embraced art depicting workers, New Masses was also working to redefine artists as workers as it attempted to create a publication for, by, and about workers. In a section at the end of each issue that gave biographical information for each contributor, artists were routinely referred to by their trades or day jobs first. Now-renowned muralist Anton Refregier was referred to as a textile worker, dishwasher, bakery worker, house painter, and “Jack of all Trades,” before his work as a New York artist was mentioned. Painter Louis Lozowick was identified as a “worker, globe trotter, student and incidentally artist;” illustrator Hugo Gellert as a ditch digger, mule skinner, cotton picker, and teacher.39

During the affluent years of the Roaring Twenties, New Masses was able to sustain its publication and keep its audience engaged with lengthy, abstract discussions about the idyllic future of an American workers’ culture and debates about the merits of being aligned with the Soviet Union. But as it became clear in the early 1930s that the Great Depression was only going to get worse, artists—and a lot of other workers—found that urgent action and organization would be required to have any hope of surviving.

40 Michael Gold, “Let It Be Really New!” New Masses, June 1926, 20.

This is not to say that the 1920s were lucrative in any way for most artists—the artists mentioned above, for example, held manual labor jobs because they didn’t make a full living from their art, not as a means of working-class posturing. Yet early articles in New Masses strike a decidedly more esoteric tone than later issues. In a section in the June 1926 issue, writers John Dos Passos and Michael Gold, in opposing editorials—“The New Masses I’d Like” and “Let it Be Really New!”—argue ad nauseum about the future of New Masses itself. “Let [New Masses] lose ourselves in this dangerous and beautiful jungle of steel and stone. Let us forget the past. Shakespeare, Dante, Shelley and even Bernard Shaw—for here are virgin paths their feet could not have trod in time and space,” Gold rhapsodizes.40

41 Herman Spector, “Two Cities,” New Masses, December 1929, 6. 42 Herman Spector, “Two Cities,” New Masses, December 1929, 6.

Following the stock market crash in late October 1929, the magazine assumed a more austere character. Poet Herman Spector, out of work at the time, writes of the mental toll that unemployment was taking in “Two Cities,” published in the December 1929 issue. “I hardly noticed anything of what passed about me, each day I had grown more and more lackadaisical, dull, despairing. My nerve had gone, I was will-less, I had lost all self-respect. My eyes looked out with abject horror at the world, at the prospect of a lonely, degraded death…Somewhere waited a wife, somewhere two anxious little children whimpered from cold and hunger,” he mourns.41 In his lamentation, he thinks back on the jobs he had held before, embracing his identity as a worker and showing his disgust for the bourgeoisie. “A job? I thought of those I had held. In the lumber yards, twelve hours a day, the evil grub and relentless toil, on the railroads, men with arms and legs lopped off, crippled and strained, fearful of momentary dismissals…Keep your lousy jobs, shrewd sneering Bosses!”42

Not only did the editorial attitude of New Masses shift as the plight of its audience grew more desperate, but it was clear that a more purposeful organization, emphasizing artists as laborers and advocating for their needs, was required if the New York creative community was to survive.

43 Alan M. Wald, Exiles From a Future Time: The Forging of the Mid-Twentieth-Century Literary Left (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2002), 105.

The first attempt at organizing sprung directly from the headquarters of New Masses around the same time as the market crash. According to poet Norman MacLeod, many young writers liked to hang around the Manhattan offices of the magazine on 112 E. 19th Street, just north of Union Square. One day in late 1929, the managing editor at the time, Walt Carmon, unable to concentrate, told the loitering radicals to “go out and form a club.” “I’ve even got a name for you—call it the John Reed Club,” he added, a reference to the Communist activist famous for his coverage of the October Revolution in Ten Days That Shook the World.43

44 Bernarda Bryson Shahn, Oral history, interview by Liza Kirwin, April 29, 1983, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution.

Soon, at an office building two blocks east and five blocks south—far enough to get out of Carmon’s way—the John Reed Club (JRC) was founded. Aside from providing a social space for the plethora of New York leftist writers and artists, the organization’s mission was vague, seemingly disorderly and hastily assembled, which was not uncommon; Bernarda Bryson, a lithographer who would later become the Secretary of the Artists Union, recalled the proliferation of leftist organizations at this time being so great that “if there were two people, there were two organizations.”44

A short announcement of the group’s founding appeared in the November 1929 issue of New Masses, reflecting both the idealism and disorganization of the fledgling revolutionaries, and its members identities as workers:

45 “Workers’ Art,” New Masses, November 1929, 21.

The radical artists and writers of New York have organized The John Reed Club. The group includes all creative workers in art, literature, sculpture, music, theatre and the movies. About fifty members have joined. Temporary officers have been chosen. Committees are functioning. Clubrooms have been secured. The purpose of the club is to bring closer all creative workers; to maintain contact with the American revolutionary labor movement. In cooperation with workers' groups and cultural organizations discussions, literary evenings, exhibits will be organized. The organization will be national in scope. Other sections will be organized throughout the country…Steps have been taken to make immediate contact with existing proletarian groups of writers, artists and all creative workers in France, Germany, Russia and Japan. Further details as to program and activities will be announced soon.45

46 Michael Gold, “A New Program for Writers,” New Masses, January 1930. 47 Alan M. Wald, Exiles From a Future Time : The Forging of the Mid-Twentieth-Century Literary Left (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2002), 327; Donald Sloan, “‘Why Not Revolution?’: The John Reed Club and Visual Culture” (Dissertation, University of Kansas, 2004), 1. 48 Kenneth Davis, FDR, The New York Years, 1928–1933 (New York: Random House, 1994), 239. 49 Harry Hopkins, “They’d Rather Work” (Manuscript, Booth Family Center for Special Collections, Georgetown University, 1935), Box 54, Folder 11, The Harry L. Hopkins Papers, Part 1. 50 June Hopkins, “The Road Not Taken: Harry Hopkins and New Deal Work Relief,” Presidential Studies Quarterly 29, no. 2 (1999), 307. 51 Andrew Hemingway, Artists on the Left: American Artists and the Communist Movement, 1926-1956 (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2002), 85. 52 “For a Permanent Federal Art Project,” Art Front, November 1934, 4. 53 Donald Sloan, “‘Why Not Revolution?’: The John Reed Club and Visual Culture” (Dissertation, University of Kansas, 2004), 25. 54 Bernarda Bryson Shahn, Oral history, interview by Liza Kirwin, April 29, 1983, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution.

Despite its chaotic origins, the John Reed Club soon found its footing as a cultural institution, staying true to its word to organize exhibitions, sponsor lecture series, and host discussion groups. By early 1930, club members had expanded their reach and organized a music school with 100 pupils, a graphic arts course with 30 members, and a “worker’s ballet” in memory of Lenin.46 At its peak, it boasted over thirty chapters nationwide, with some historians citing it as one of the most successful American Communist cultural organizations.47

By this time, the Depression had sent the country into economic disarray. The national unemployment rate was nearly twenty percent and in New York State alone, one million workers were unemployed.48 Social worker Harry Hopkins, who would later become the director of many of the New Deal work programs, recalled that it seemed like “almost every time the clock ticked a man lost his job.”49

While some work programs existed in New York City in the first few years of the Depression, they were usually temporary and privately funded. The Emergency Work Bureau (EWB) was one such example; it was created in 1930 only after Hopkins and colleague William Matthews solicited $6 million in private donations to pay approximately 100,000 people to work in city parks, painting fences and trimming bushes three days a week.50 In December 1932, the first jobs program specifically for artists to work in their field was created as part of the EWB, but paid only 100 artists a paltry average of $260 ($5,000 in 2021 dollars) over the course of a year.51 Because, as outlined above, most artists did not make their living solely through their art, the program was not expected to be a complete income replacement. Government patronage in any capacity was a new concept, however, and laid the groundwork for more artists to campaign for the ability to make a living only through their artwork.52

As much of the artistic community continued to plummet into the depths of economic misery, the limits of the JRC became apparent. For all its cultural influence, its members did not see it as an organ for political organization, perhaps deliberately; many of the JRC founders were intent on keeping the club strictly a social and cultural space. Moreover, artists in the JRC were declining as a percentage of overall members; it is estimated that by the beginning of 1934, only a small minority of the JRC were visual artists, compared to writers or other creative workers.53 In fact, Bernarda Bryson felt that artists were no longer being respected as independent thinkers. “The attitude in the John Reed Club was that you really should take orders as an artist. You should do work that is dictated by [the Communist Party], almost literally,” she remarked in a 1983 interview, adding that artists, even more than writers or other creative workers, were only supposed to visually depict “the chosen causes.”54 New York artists needed a group dedicated to artists, their economic needs, and their freedom of expression and identity.

55 “History of the Artists Union,” Art Front, November 1934, 4.

The elimination of the EWB’s art project in the summer of 1933 provided the impetus for yet another new organization. On September 24, 1933, about twenty-five of the artists previously employed by the EWB formed the EWB Artists Group, which was later named the Unemployed Artists Group. Its early leaders included Max Spivak, Phil Bard, Boris Gorelik, Bernarda Bryson, Stuart Davis, Michael Loew, James Guy, and Joseph Vogel—almost all of whom were members of the JRC and had been editors or contributors for either New Masses or The Liberator. Initially, they met at a different hall or office space each week, picking up new artists each time as they wandered throughout Greenwich Village and the Lower East Side of Manhattan, before finally settling at 11 West 18th Street, just a few blocks south of the Flatiron Building. Now composed of both employed and unemployed artists, the name changed once more; the group was now known as the Artists Union. The group built upon New Masses and the JRC’s close alliance with the American labor movement in the most logical way possible: they became part of it. Motivated by “the realization that only the artist can define the artist’s needs and the conditions necessary for his maintenance as an artist,” artists began to pursue the possibility of making their living only as artists, an important step to defining themselves as workers.55 In short, the more artists who could survive without having other jobs, the more art would be seen as a distinct vocation on par with other forms of labor.

56 Gerald M. Monroe, “The Artists Union of New York” (Dissertation, New York, New York University, 1971), 54. 57 Phrase adopted from Gerald M. Monroe, “The Artists Union of New York” (Dissertation, New York, New York University, 1971), 54.

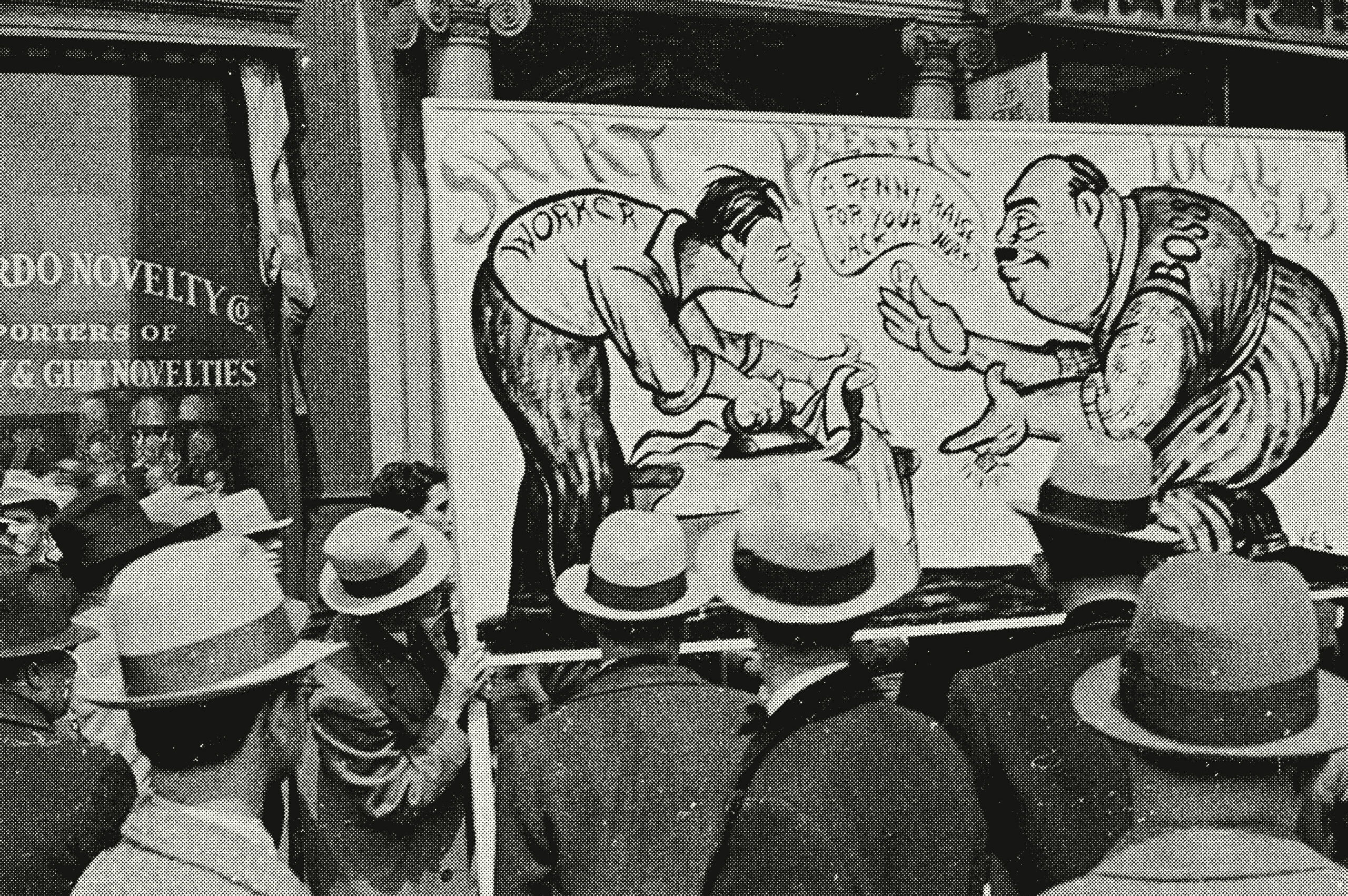

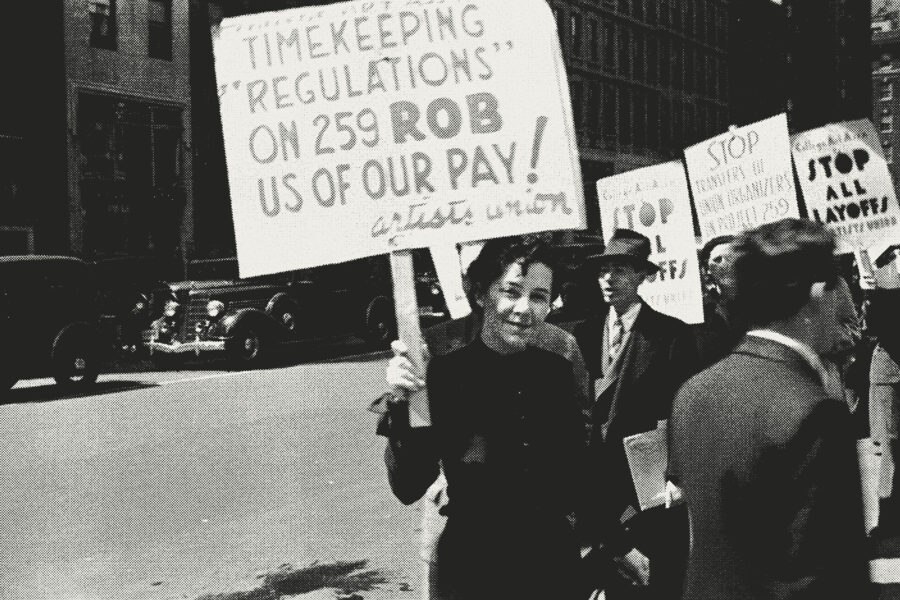

Eager to prove their solidarity and more closely align themselves with workers who might otherwise dismiss a group of artists, Artists Union members often participated in other union demonstrations or on picket lines besides their own, eventually earning them the nickname “the fire brigade.” Joining in was never a requirement imposed by the union’s leadership, but that wasn’t necessary—many members felt showing solidarity was important to earn allies and contribute to the larger community of organized laborers, so just a suggestion from the board or an appeal made from a member or a visitor during a weekly meeting was enough, according to artist and Artists Union member Norman Barr.56 When protesting for their own causes, Artists Union members knew that they wouldn’t receive contractual rights in the same way that a typical union might from a private company, as they were fighting for relief programs from municipal, state, and federal governments, but participating in the actions of organized labor drew parallels that they felt bolstered their identity as “cultural workers.”57

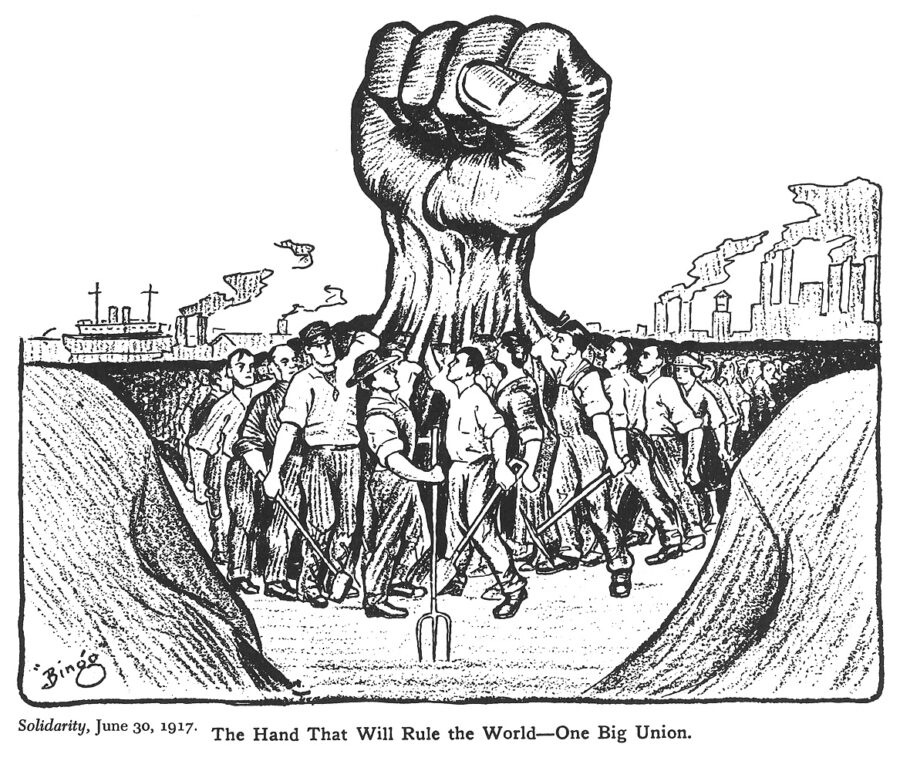

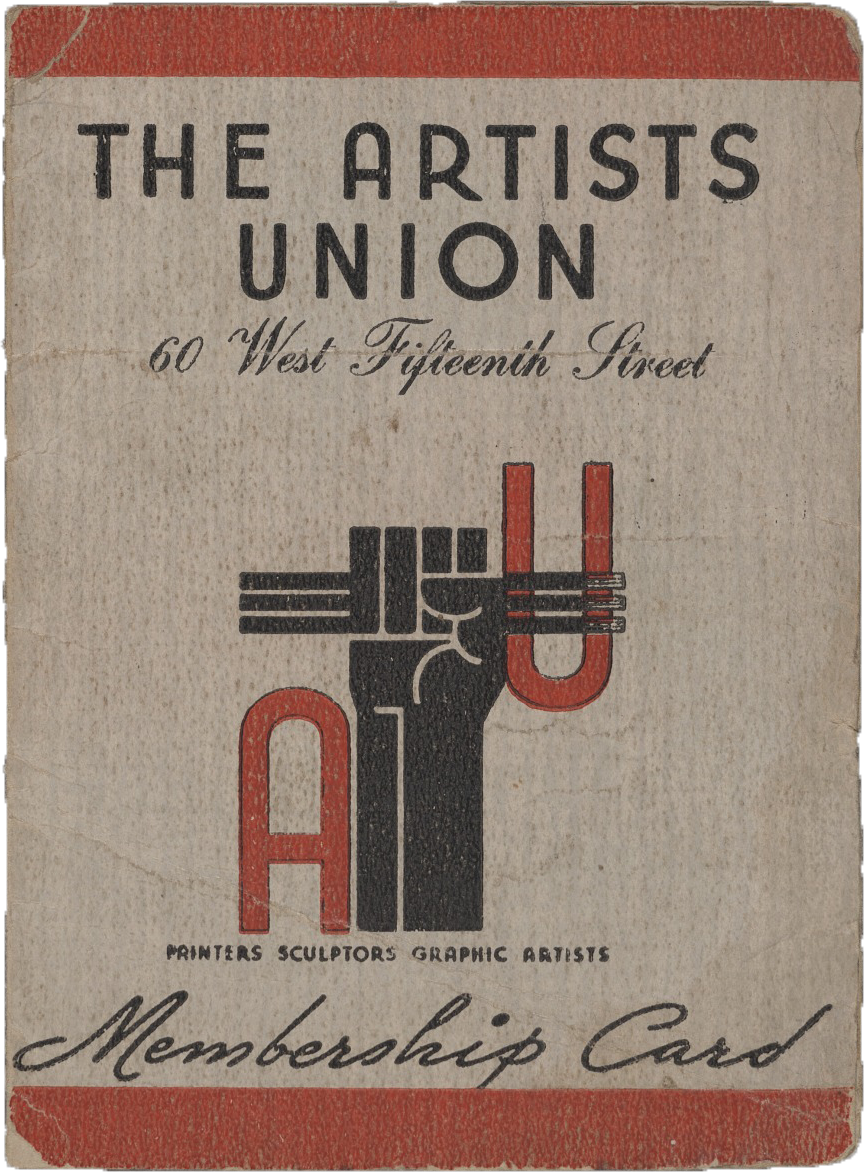

58 Harry Gottlieb’s Artists’ Union Membership Card, 1935, 11x17 cm, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution. 59 James Stout, “The History of the Raised Fist, a Global Symbol of Fighting Oppression,” National Geographic, July 31, 2020. 60 Ralph Chaplin, The Hand That Will Rule the World—One Big Union, Cartoon, Solidarity, June 30, 1917.

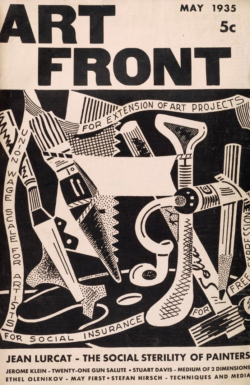

The fact that the Artists Union’s members identified as workers soon showed itself in the organization’s visual culture. The Artists Union logo, which appeared on the membership card and on multiple front covers of Art Front, consists of a geometric representation of a closed fist holding three paintbrushes with “A” and “U” on either side.58 The design references the raised fist that was first used by International Workers of the World (IWW) founder Bill Haywood during the 1913 silk strike in Paterson, New Jersey. “Every finger by itself has no force,” he said, lifting his open hand. “Now look,” clenching his fingers into a fist. “See that, that’s the IWW.”59 The symbol was later popularized in a cartoon by Ralph Chaplin that appeared in a 1917 issue of the IWW’s newspaper Solidarity, showing the arms of hundreds of workers connecting to become a giant fist, and had by 1933 become an instantly recognizable sign of collective power and protection.60

61 Stuart Davis, “Cover,” Art Front, May 1935, 1.

Members of the Artists Union continued to demonstrate their identity as workers in visual communications by emphasizing that artists, like other industrial workers, labored with their hands. The May 1935 cover of Art Front, designed by Stuart Davis, featured many of the tools of the trade, including a pencil, palette and palette knife, paint, punch awl, saw, and a hammer on which “Solidarity” is inscribed. A banner, which weaves throughout the tools around the border of the work, reads “Union wage scale for artists…For social insurance…For extension of art projects…For free expression,” demonstrating union members’ demand to be paid at the same rate as other unionized laborers while still maintaining their trade-specific demands and ideological stances. In case the artist-as-worker message still wasn’t clear, Davis included a banner in the middle of the drawing with “May 1” written on it, a celebratory reference to International Workers’ Day.61

62 Boris Gorelick, Oral history, interview by Betty Hoag, May 20, 1964, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution.

These prominent visual expressions demonstrate not only how the members of the Artists Union perceived themselves, but also their intent to communicate that identity to the broader art and labor community and gain widespread recognition as laborers. While the exact circulation of Art Front is unknown, one member recalls it being “fairly wide,” adding that the magazine was sold all over the country, although its influence was greatest in New York City.62

63 Frank L. Kluckhohn, “Uncle Sam Expands as an Art Patron; With His Aid Thirty Thousand Creative Workers Are to Carry Culture to Every Comer of the Country,” The New York Times, October 6, 1935, 5; “For City Aid to Artists: Deutsch Sees Help for Creative Workers a Possibility,” The New York Times, March 9, 1934, 17; “For a Permanent Art Project,” Art Front, November 1934, 4. 64 “The Union Applies for an AFL Charter,” Art Front, July 1935, 2. 65 Gerald M. Monroe, “Artists as Militant Trade Union Workers During the Great Depression,” Archives of American Art Journal 49, no. 1/2 (2010): 51; Elinor Waters, “Unionization of Office Employees,” The Journal of Business 27, no. 4 (1954), 285. 66 Deborah Mutnick, “Toward a Twenty-First-Century Federal Writers’ Project,” College English 77, no. 2 (2014): 124–45.

At the same time as the magazine was asserting, in words and pictures, that artists are workers, other media and other unions began to reflect the change in thinking. The New York Times, who had previously placed artists under the umbrella of the “white-collar” federal relief program, began using the term “creative worker” to refer to artists in 1934, the same descriptor that many members of the Artists Union used.63 Most importantly to members of the Union, they were accepted by fellow workers. Beginning in the spring of 1935, the union pursued affiliation with the American Federation of Labor (AFL) to strengthen its leverage when fighting for permanent government patronage but was denied. The refusal was likely not because the artists weren’t seen as workers, but because the AFL was conservative at the time and resisted welcoming a staunchly leftist union, although the Commercial Artists and Designers Union (CADU), which maintained close ties with the Artists Union, was granted an AFL charter.64 Two years later, however, the union found an ally in the Congress of Industrial Organizations (CIO), which was increasing in size and influence and was much more welcoming of more radical organizations. The Artists Union, the CADU, and the small Cartoonists Guild combined to form the United American Artists in January 1938, becoming Local 60 of the CIO-affiliated United Office and Professional Workers of America, a union known for combining “elements of both craft and industrial structure.”65

In the end, it may have been the hardships of the Depression that destroyed previous distinctions between artists and other manual laborers. The economic distress of artists, so similar to that of other workers, forced the broader public to see them as the same, or at least to define creating art as similar to other types of labor, especially when artists were forced to take on additional jobs to earn a living. As WPA Director Harry Hopkins said when challenged on the legitimacy of relief for creative workers, “Hell, they’ve got to eat, too.”66

67 “The Commercial Artist,” Art Front, January 1935, 5.

Undoubtedly, the pro-working class, leftist ideology of many union members was a primary driver in their desire to have artists recognized as workers. But the strategy also bolstered the union’s goal of having local, state, and federal governments create work-relief programs specifically for artists. Since artists were workers, they argued, they should have access to programs identical to the Public Works Administration or the Civil Works Administration that were be created for industrial laborers. In addition to addressing the immediate financial peril of many artists, these artist-specific New Deal relief programs offered another element of worker identity—non-commercial, gallery artists would now work in situations defined by the employer-employee relationship present in so many other industries, rather than at the mercy of private patronage. This would help them further establish solidarity with other parts of the labor movement, as the Artists Union would now have to contend with bosses, timecards, wages, and all of the grievances that conventional unions work to remedy. A small section of the union, made up of commercial artists that worked at advertising agencies, were already experiencing how artists in traditional workplace structures were identified similar to other workers. In a January 1935 announcement of a specific section of the union devoted to commercial artists, the workplace conditions described could easily apply to say, a steel or auto worker, especially during the high unemployment of the Depression. “Continually on the alert, the employers are aware of the swollen army of unemployed artists. They utilize this very situation to force employed artists to accept without a murmur of protest such conditions of employment as lowered wages, unpaid overtime, and speed-up.”67

The rest of the Artists Union, made up of non-commercial artists, was firmly aware of the exploitative nature of the employer-employee relationship, both because of their theoretical understanding of Marx and his analysis of the proletariat and bourgeoisie, and their practical experience with the commercial artists section, workers in other industries, and artists who held other jobs to make a living. The economic devastation of the Depression, however, made the conditions of traditional workplace structures preferable to the reality of the rest of the union, made up of gallery artists. If those artists were part of the WPA program, they would be subject to mistreatment by managers and administrators, to be sure, but they would also be put on a payroll with a steady, guaranteed income. The alternative was private patronage, the loathed, fickle and exploitative system that dominated the art world and was increasingly unsustainable as the Depression deepened. For both economic and ideological reasons, the Artists Union was committed to eliminating private patronage and moving art away from the sphere of the wealthy elite and into the public domain where all Americans could enjoy it in their everyday lives.