CHAPTER THREE

SCREENPRINTING

& BRINGING ART

to the PEOPLE

133 “Harry Gottlieb Is Dead; W.P.A. Artist Was 98,” The New York Times, July 8, 1992, sec. Arts, 18; “Call for an American Artists’ Congress,” Art Front, November 1935, 6. 134 Gerald M. Monroe, “The Artists Union of New York” (Dissertation, New York, New York University, 1971), 98.

If there were an archetypal Artists Union member, it was Harry Gottlieb. Born in Romania in 1895, he emigrated to Minneapolis with his family at age 11. After studying at the Minneapolis Institute of Arts for a few years and then moving to New York in 1918, he began to follow the usual career trajectory of a radical artist. He eked out a living as part of the artist’s colony near Woodstock, NY for more than a decade and eventually managed to secure some private patronage in the form of a Guggenheim Fellowship to study for a year in Europe. Upon his arrival back in New York City, he found himself out of work and joined the Artists Union soon after its inception in 1934, first appearing on the pages of Art Front in November 1935.133 The next year, he was hired by the Graphics Division of the Federal Art Project. Seen as a model for the union’s vision of a government-funded artist because of his extraordinary artwork and commitment to furthering the cause of all workers, and well-liked by his peers, he was elected as the Artist Union’s president in 1936.134

135 Anthony Velonis, Oral history, interview by Harlan Phillips, October 13, 1965, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution.

Later that year, a painter and designer named Anthony Velonis who had been working in the FAP’s poster division suggested to administrators that the unit could be much more productive if there were a separate screen-printing project that worked alongside it, as screen-printing was a much faster and cheaper method of printmaking. It could, he said, help expedite the poster-making process if the design and production of the posters were separated. After Velonis presented some experimental test prints to prove the technique’s value, administrators agreed, and Velonis was charged with assembling a team of six artists. Because of Gottlieb’s proven success with lithography, another form of printmaking, Velonis chose him as one. Perhaps inadvertently, Velonis established the new division as a union shop, rounding out the team with Artist Union members Louis Lozowick, Eugene Morley, Hyman Warsager, Carl Zigrosser, and Elizabeth Olds.135 As a small division, the Silk Screen Unit, as it was officially known, didn’t receive much attention from the broader union in Art Front, but is nonetheless a case study of how artists involved with the Artists Union changed American ideas about art and work. Many, if not all, of the artists held leftist and Communist beliefs and made cultural productions that glorified the proletarian manual laborer and their place in society. Thanks to the WPA’s network of community art centers, their government-funded works were viewed by people all across the country.

Of course, artistic depictions of work have existed for centuries, and even depictions of industrial labor were nothing new by the time of the Great Depression—The Liberator, New Masses, and the other leftist magazines discussed in Chapter One included plenty of cartoons and drawings with workers as the focus. Through the FAP, however, four elements were different: there was more artwork produced than ever before in American history, that art was made readily accessible to people that had no prior experience with fine art in their daily lives, the work was funded by the federal government, and the artists making those works were actively engaged in a leftist political movement that influenced their art. This meant that Gottlieb and other Artists Union members helped bring cultural productions that valorized labor and laborers to everyday people, across the country, for the first time in American history.

136 Mary Francey, “American Printmakers and the Federal Art Project,” Resource Library, October 18, 2008. 137 Anthony Velonis, Oral history, interview by Harlan Phillips, October 13, 1965, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution.

In addition to fulfilling its mandate to supplement the poster project, the Silk Screen Unit was drawn to exploring the medium’s potential because it was a still a relatively new technology and had not been used much outside of advertising or commercial applications.136 In many ways, screenprinting was the perfect medium for artists looking to bring art “into the hands of the public” because it was a fast, low-cost, and easy way to mass-produce images. For Velonis and the six union members, drawn to depictions of workers and labor, screen printing was especially fitting because its multi-step, repetitive process mirrored many of the industrial advances like the specialization of labor and assembly lines that were pushing workers in machine-like ways. As Velonis put it, “[screen-printing] is a great medium for the artist. Look what it can do -- with the least possible expense you can make all kind of things.”137

138 Helen Langa, Radical Art: Printmaking and the Left in 1930s New York (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2004), 55. 139 Helen Langa, Radical Art: Printmaking and the Left in 1930s New York (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2004), 107–108.

Screenprinting’s industrial-like process gave Gottlieb and his fellow Silk Screen Unit members the opportunity to create art that demonstrated solidarity with their fellow laborers. As a lifelong affiliate of the Communist Party (although he never openly acknowledged it), Gottlieb was drawn to furthering the cause of the proletariat, and workers became a central focus in his prints and paintings.138 In the spring of 1936, Gottlieb and Olds traveled to eastern Pennsylvania to visit a mining town where striking coal miners had been fired by owners that refused to negotiate a new union contract. In response, the miners created a “bootleg operation” to dig coal from the surface seams and sell it. When Gottlieb and Olds arrived, the miners, understandably reluctant to trust outsiders, demanded that the pair of artists drive to a nearby town to join their union before making any work.139 Their willingness to do so is an indication of the ways in which they and other Artists Union members were changing ideas about art and artists on an interpersonal level by proving their solidarity with the working class in tangible ways that went even beyond their regular support of other labor unions discussed in Chapter One.

140 Harry Gottlieb, Mine Disaster, Screenprint, 1939, National Gallery of Art.

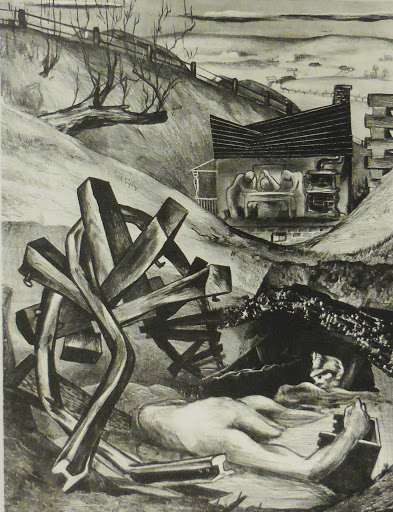

The trip to Pennsylvania certainly influenced Gottlieb, who continued to show his solidarity in the way he depicted the miners he had met. In his 1939 screenprint Mine Disaster, he shows a large crowd of people gathered around a coal mine. Fellow miners, men, women, and children with anxious faces surround the entrance to the mine, pointing downward at some sort of accident, while others hurriedly rush to get the attention of others in the background, where there is also a fire ablaze. Again, while its clear that the people are involved are miners, coal is not actually shown–the emphasis is not on the product, but on the people who make it happen. Mine Disaster doesn’t glorify the work of miners but evokes the danger and hardship they face to provide essential heat and electricity—they are isolated from society for long periods of time, away from their families in town and even far away from the factory in the print’s background, going deep underground to scrape away at the earth in precarious mines. The print’s grim yet realistic depiction of the miners, who are inked in various shades of grey, highlights their value to society, even if society doesn’t value them enough to keep them safe. Moreover, the grief of the women in the lower left, the confused children in their parents’ arms, and the fellow miners with stoic yet concerned faces who have seen this scene before and assume the worst all contribute to the screenprint’s sense of community in the face of disaster. Gottlieb’s characters, although simple and not photorealistic, convey an undeniable sense of humanity, and their connection to one another is palpable.140

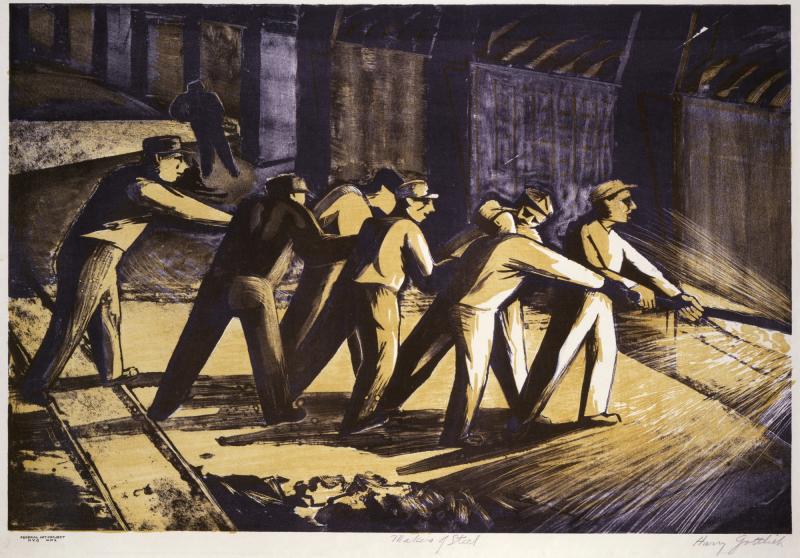

141 Harry Gottlieb, Makers of Steel, Color lithograph, 1937, Smithsonian American Art Museum.

Another example of Gottlieb’s depiction of workers is his 1937 color lithograph titled Makers of Steel, in which he depicts a group of steelworkers in a dark factory, dramatically illuminated by the light and sparks of the forge. The group of seven men are wearing monochrome clothing and caps, all with broad frames, hunched over along a rod of iron. Notably, Gottlieb omits from the scene the metalworking furnace where the iron is actually being forged—the workers are the center focus and take up nearly the entire print. It’s clear that the men are doing some sort of manufacturing, but Gottlieb is not focusing on the product that is being made, instead reminding the viewer of the workers and their physical toil that are essential to infrastructure.141 He also makes a point to show the men working together with none of their faces especially distinct, demonstrating that their strength and ability to forge both steel and working-class power comes as a united, equal group.

142 Harry Gottlieb, The Strike Is Won, Screenprint, 1940, Flint Institute of Arts.

Gottlieb was committed to accurate depictions of working life, and while that often meant illustrating the backbreaking labor and danger that accompanied many industrial jobs, it also sometimes offered the chance to show a triumphant occasion. His 1940 screenprint The Strike is Won shows a group of workers whose strike has been successful, some embracing each other, some with arms raised in the air, and some shouting and proudly holding picket signs. Gottlieb includes workers of all ages, races, and ethnicities, emphasizing the ideal of working-class solidarity. An older, gray-haired worker in the lower right is particularly striking, as his face of complete disbelief instantly conveys how difficult and long labor struggles can be—one can imagine the years of fighting the man has endured.142 This print is also noticeably more colorful and vibrant than his industrial scenes, underscoring the feeling of joy that stands in contrast to the toil and grief that workers often endured.

143 Hyman Warsager, Gathering Logs, Screenprint, 1937. 144 Elizabeth Olds, 1939 A.D., Lithograph, 1939, Smithsonian American Art Museum.

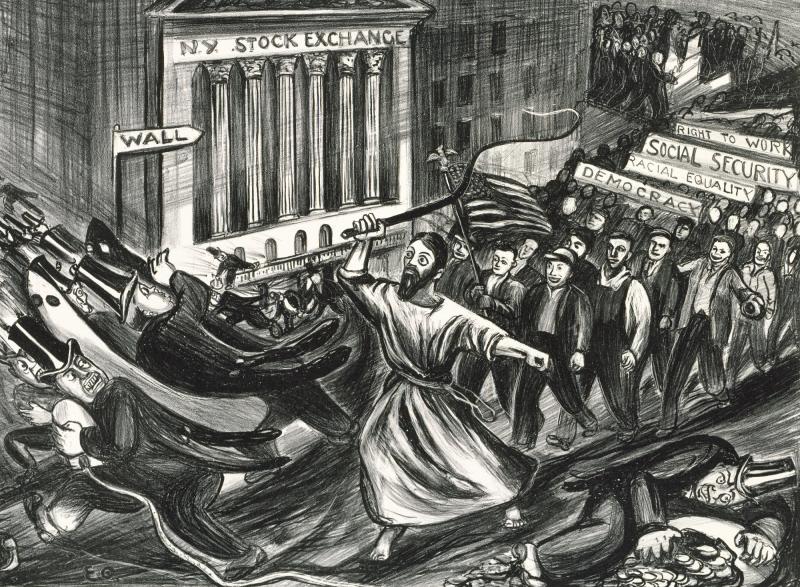

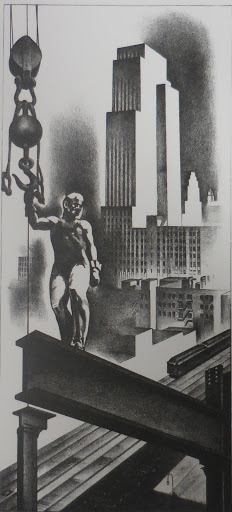

Gottlieb was far from the only screenprinter producing this kind of work. The other five artists in the Silk Screen Unit, each with their own styles, echoed his ideas about workers and their place in society. Warsager, in his 1937 screenprint Gathering Logs, for example, follows the same social realist, authentic depictions of manual labor, emphasizing the people and effort required to create the essential infrastructures of society that many take for granted.143 Lozowick preferred to work in urban settings, often depicting construction workers dramatically set against skyscrapers, bridges, and transit stations. Olds, while often creating real-life scenes like Gottlieb and Warsager, sometimes decided to be more overt, such as her print 1939 A.D. A contemporary interpretation of the biblical story of the Cleansing of the Temple, in which Jesus expels the merchants and moneylenders from the Temple in Jerusalem, the print shows Jesus cracking a whip to drive out the Wall Street capitalists from the New York Stock Exchange as he is followed by protesting workers with signs that read “Democracy, Racial Equality, Social Security, and Right to Work.”144

145 Joseph Leboit and Hyman Warsager, “The Graphic Project: Revival of Print Making,” Art Front, December 1937, 9 146 Joseph Leboit and Hyman Warsager, “The Graphic Project: Revival of Print Making,” Art Front, December 1937, 9 147 Joseph Leboit and Hyman Warsager, “The Graphic Project: Revival of Print Making,” Art Front, December 1937, 9 148 Joseph Leboit and Hyman Warsager, “The Graphic Project: Revival of Print Making,” Art Front, December 1937, 10.

The pioneering Silk Screen Unit helped launch a whole movement of leftist printmaking within the FAP, including Anton Refregier, Leon Bibel, and dozens of other Artists Union members. These artists, using the patronage of the WPA that they had fought so hard to obtain, were able to exhibit their work in nearly every corner of America, allowing ordinary people to see their art and absorb the leftist, pro-worker ideas behind it. By the end of 1937, from the New York division of the FAP alone, 2,693 prints had been allocated to public buildings on a 99-year loan. Five thousand one hundred and eighty-seven prints from the New York division were sent to the federal offices of the WPA, where some, along with work from other divisions, were distributed to educational institutions. Others were “not given much chance to collect dust either,” as they were shipped across the country as part of hundreds of traveling exhibitions that visited various art and cultural centers.145 In New York City, 33 of these exhibits, showing about 700 prints total, were arranged just between January and August of 1937. Instead of being shown at “uptown, high-hat galleries,” art was brought directly to the people; shows were held, for the first time, at settlement houses, hospitals, schools, and public universities.146 The Artists Union’s Public Use of Art Committee took it a step further, providing the funding and support to show the exhibitions at numerous trade union halls, which “received them with enthusiasm.”147 The art press concurred with the unions’ verdict—The New York Post upheld the prints as “art that deserves to go permanently to the people,” proclaiming that “WPA artists have created vigorously out of the experiences most congenial to them;” the New York Herald Tribune reviewer was captivated by the “careful and imaginative work and excellent technique;” and The New York Times concluded, “Of the exhibit let it be said at once that there are some thoroughly good and robust things.”148

149 “The Lag in the WPA,” Art Front, December 1935, 3. 150 Helen A. Harrison, “Subway Art and the Public Use of Arts Committee,” Archives of American Art Journal 21, no. 2 (1981), 3.

The exhibitions were not the only way that Artists Union members helped to change American norms about art and labor. At the same WPA art centers where prints were being exhibited, FAP-employed artists were teaching art classes and lessons, open to all people. Hundreds of Artists Union members from chapters outside of New York were employed teaching nationwide, especially in Boston, San Francisco, Cleveland and Detroit.149 In New York alone, dozens of Artists Union members on the FAP were part of Project 1259, a program to teach art classes in community centers, settlement houses, and welfare institutions.150

151 Virginia Hagelstein Marquardt, “The American Artists School: Radical Heritage and Social Content Art,” Archives of American Art Journal 26, no. 4 (1986), 17. 152 Virginia Hagelstein Marquardt, “The American Artists School: Radical Heritage and Social Content Art,” Archives of American Art Journal 26, no. 4 (1986), 22.

Even outside of the WPA, Artists Union members found ways to influence future generations of artists. Gottlieb, Olds, Warsager, painters Stuart Davis and Phillip Evergood, historian and critic Meyer Schapiro, and countless other union members either taught or were on the advisory board of the American Artists School, an independent art school that was founded in New York in 1936. The school approached art education by “combining training in techniques with the study of social issues for young artists, mainly workers, who needed some training to qualify for federal arts program.”151 Although the school was only in operation for about five years, historian Virginia Marquardt upholds it as a “pioneer in freeing its students and faculty from dogmatic and stereotyped approaches to art and in fostering a people’s art.”152

Through the FAP-funded movement sparked by Harry Gottlieb and his fellow screenprinters, ordinary American workers saw for the first time depictions of their lives in art made by professional artists. This cultural shift in what American art represented and who it was made for changed norms not only for the artists who earned a living from their work, but also for ordinary people. For the first time, workers and their families could see themselves in art, and thanks to WPA-funded art education, have the opportunity to become artists themselves, shattering the pre-Depression norms that art was something produced by elites, for elites.

153 John Ross, Claire Romano, and Tim Ross, Complete Printmaker (New York, Simon and Schuster, 2009), 145. 154 “Max Arthur Cohn,” Smithsonian American Art Museum, accessed April 23, 2021.

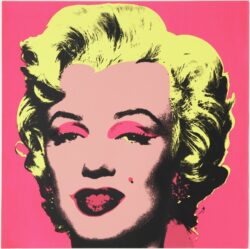

As Artist Union members were changing American norms about the place of art and workers in society, they were also transforming the art world by introducing screenprinting as a legitimate, widespread technique in fine art. In 1940, Velonis, Warsager, Tom Quinn, another union member, and WPA artist Max Arthur Cohn, having spent the previous four years experimenting and pioneering screenprinting as a medium, founded the National Serigraph Society (NSS) to further support and promote printmakers using the screenprinting process. The organization, whose name was invented by Velonis and Cohn to differentiate the artistic use of screenprinting from industrial and commercial applications, distributed a quarterly newsletter, held lectures, and organized traveling shows.153 While the NSS ceased to exist by 1962, their efforts to foster screenprinting proved to be hugely influential. Cohn, for example, owned a graphic arts business in New York during his tenure at the NSS, and is credited with teaching the screenprinting process to a young artist named Andy Warhol during the 1950s.154 Screenprinting went on to take the pop art movement by storm and was used heavily by Roy Lichtenstein, Jasper Johns, Robert Rauschenberg, and countless others to create—much like the FAP artists—fine art that was accessible to everyday Americans.